Thank you for reading Observing Japan. This post is available to all readers.

If you are looking for timely, forward-looking analysis of the stories in Japan’s politics and policymaking that move markets, I have launched a new service through my business, Japan Foresight LLC. For more information about Japan Foresight’s services or for information on how to sign up for a trial or schedule a briefing, please visit our website or reach out to me.

While the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and Kōmeitō losing their majority in the House of Representatives was the single most important development in Japanese politics in 2024, it is increasingly apparent that 2024 will be remembered above all as the year in which social media truly arrived in Japanese politics.

Ishimaru Shinji’s surprising second-place finish in Tokyo’s gubernatorial election in July, a crowded LDP leadership election dominated by YouTube and Twitter, the surge in support for the Democratic Party for the People (DPFP) in the October general election, Saitō Motohiko’s unlikely comeback in the snap election to fill the Hyogo governorship he vacated: all suggest that Japanese politicians have come to see the power of social media in amplifying their messages, disrupting the status quo, and outmaneuvering candidates and parties dependent on more traditional modes of campaigning. There is a distinct sense that we have only seen the beginning of the Online era of Japanese politics, with unforeseen consequences for how the country will be governed.

In the not-too-distant past, Japanese elections were strictly analog. Candidates were strictly regulated in how they could communicate with voters during campaign periods, and elections looked much as they had for decades.

Then, in 2013, the Diet passed a bill lifting most restrictions on the use of the internet – including personal websites, video sharing, and social media sites – during campaigns, marking the beginning of the period of “net elections.”1

For most of the past decade, these communications tools largely supplemented traditional ways of campaigning. Candidates and parties shared video ads and used their websites to provide information about where party leaders would be campaigning, but there is little sense that these tools fundamentally altered the practice of electioneering. Outside of elections, there were signs that politicians recognized the Internet’s potential as a tool for influencing – or manipulating – public opinion, particularly through the LDP’s ties with the online right (netto-uyo) or the incident of its relationship with the “Dappi” Twitter account.2 But generally speaking, Japanese political communications still remained heavily analog.

To some extent, the discourse about social media in politics is focusing on a symptom instead of an underlying cause. As I wrote following Saitō’s victory in November, “The ability of certain politicians to mobilize otherwise disaffected voters through social media is a potent demonstration of the existence of a disgruntled minority that feels excluded from political power.” Social media has revealed the existence and possible scale of a bloc of voters, particularly concentrated among the young, who feel largely excluded from the political status quo, underrepresented and underserved by the political establishment. As Seikei University Professor Itō Masaaki explained to the Asahi Shimbun, this looks like an urban-centered youth revolt against “silver democracy,” against entrenched elites who are simultaneously blocking policies that would create a more robust safety net for the young while also facilitating greater innovation and creavitity. Social media did not create this phenomenon, but it has, in capable hands, been useful for mobilizing it.

While Japan has had disaffected youth before, there is a growing sense among older Japanese that younger Japanese are increasingly “unmoored” from broader society. As Kawato Akio, a foreign affairs commentator and former Japanese ambassador to Russia wrote in June, “They don’t read newspapers. They don’t watch TV. They don’t vote. The social, political, and economic infrastructure and systems that have been in place until now seem to young people to be quite rubbish, false, illogical, and absurd.” The consequence, Kawato writes, is that many young people are “liberated” from the institutions that have structured Japanese life for generations. If, as Benedict Anderson famously argued, media is how nations imagine themselves, young Japanese are increasingly opting out of the imagined community.

The 2024 edition of the Japan Press Research Institute’s annual survey of media consumption habits of the Japanese people shows, in addition to falling media consumption across the board, not only widening age gaps in what media different generations consume but also in the degree of trust in different media institutions. Trust in NHK, newspapers, and commercial television rises together with age; trust in the internet is inversely correlated with age.

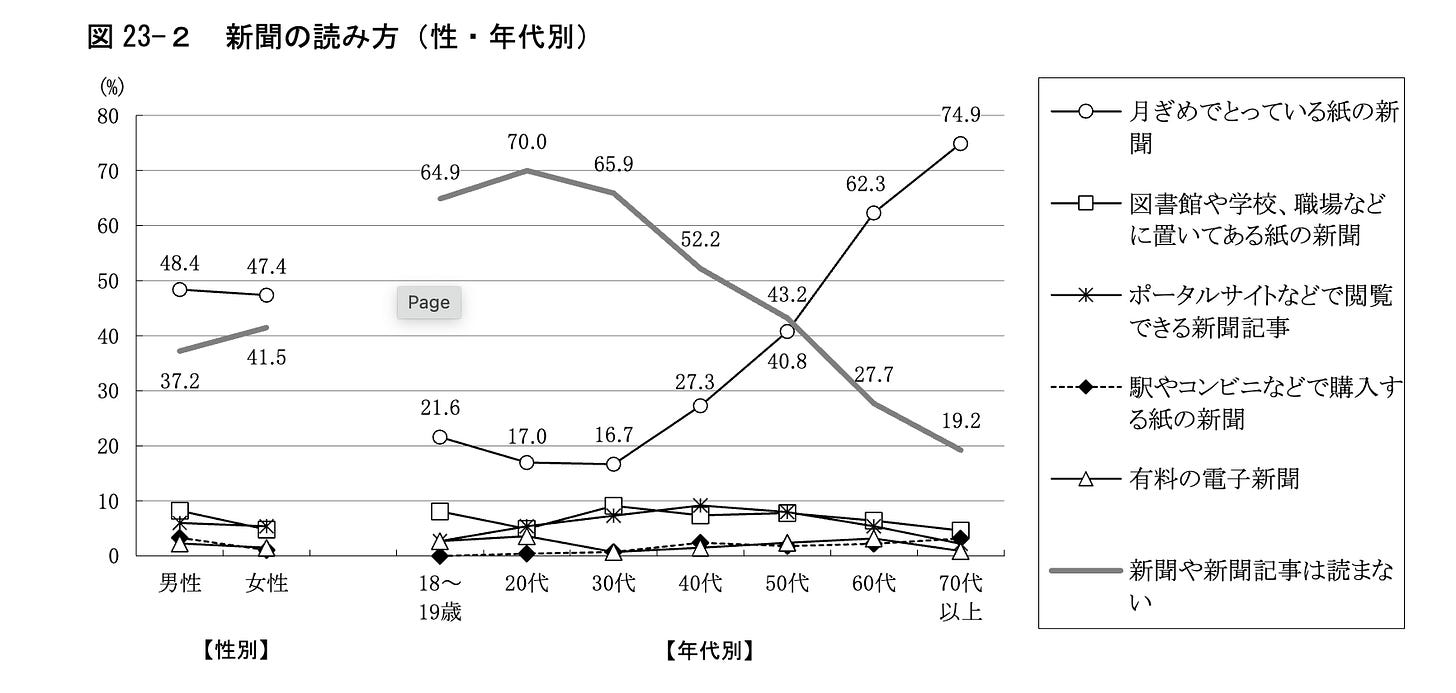

Newspaper readership, which has held up better for longer in Japan than in its peers in the developed world, has plummeted among young Japanese, who, like young Americans and Europeans, are turning to social media for information. The survey found that 64.9% of 18 and 19 year olds, 70% of those in their twenties, and 65.9% of those in their thirties do not read newspapers or newspaper articles.

Virtually no young people are using the internet to read the websites of traditional print and broadcast news organizations: only 5.9% of 18 and 19 year olds, 7.6% of those in their twenties, and 8.4% of those in their thirties visit these sites, versus 76.5%, 73%, and 55.7% who visit social media.3

While these changes in Japan’s information environment suggest a convergence with its peers, it nevertheless marks a significant change for, among other things, how Japanese democracy will work. Japanese politicians and parties will have to become more adept at using social media because increasingly that is where the voters will be.

However, the LDP’s response to Japan’s year of Online elections has been to start a discussion of how to regulate the use of social media during campaigns. As Noda Seiko, who chairs the LDP’s telecommunications strategy committee, said, “The electoral system is analog. We need to reevaluate everything, but we must grapple with the use of social media for electoral activities that provide information to voters without just saying ‘social media is bad.’” The party’s electoral system committee has been meeting to consider regulations to combat the dissemination of false information via social media, including the possibility of penalties for candidates who disseminate false information or slander their opponents.

The party seems to recognize that this is an extraordinarily difficult challenge on both constitutional grounds but also practical grounds, not least since they would have to convince non-Japanese social media companies to comply with any regulations but also since plenty of political information (and dis- and misinformation) spreads organically, without the involvement of candidates and campaigns. Despite these obstacles, there is extraordinary public interest in social media regulations. In the latest Yomiuri Shimbun poll, 74% of respondents think it is necessary to prevent social media abuses during campaigns. In Kyodo News, 85.5% said that they think slanderous or false information on social media during campaigns is a significant (49.1%) or moderate (36.4%) problem.

Having watched the impact of social media on elections in other democracies, the impulse to regulate social media’s use in Japanese political life before it becomes more deeply integrated is understandable, even if it feels like this discussion should have begun much earlier. Still, it is appropriate for Japan’s politicians to question whether an institution that in other democracies has been a vector for malign actors – foreign or domestic – to influence elections should be left unregulated.

That said, I fear that the LDP and other established parties could be learning the wrong lesson from the year of Online elections. The story is not that social media is having a poisonous effect on Japanese politics and needs to be restricted. Rather, the lesson is that there are too many Japanese, particularly young Japanese, increasingly feel disconnected from the political system and are not even reachable by political elites except through social media. Japanese political leaders should focus at least as much on how to build a more inclusive democracy as on how to manage the impact of social media on democracy. If they cannot, the Online elections of 2024 will be only the beginning of a turbulent era for Japan’s democracy.

The Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, which administers elections, created this pamphlet explaining the changes.

Apparently in their thirties Japanese start turning increasingly to Yahoo! and other news portals, which are extraordinarily popular with older Japanese.