Thank you for reading Observing Japan. This post is available to all readers. From now until 15 July, annual subscriptions are 20% off.

I will be launching a monthly conference call exclusively for paid subscribers this month, with the first call scheduled for 16 July. I am still interested in readers’ thoughts on how to format the conference call, so please share your opinions in the survey below.

If you are looking for timely, forward-looking analysis of the stories in Japans’s politics and policymaking that move markets, I have launched a new service through my business, Japan Foresight LLC. For more information about Japan Foresight’s services or for information on how to sign up for a trial or schedule a briefing, please visit our website or reach out to me.

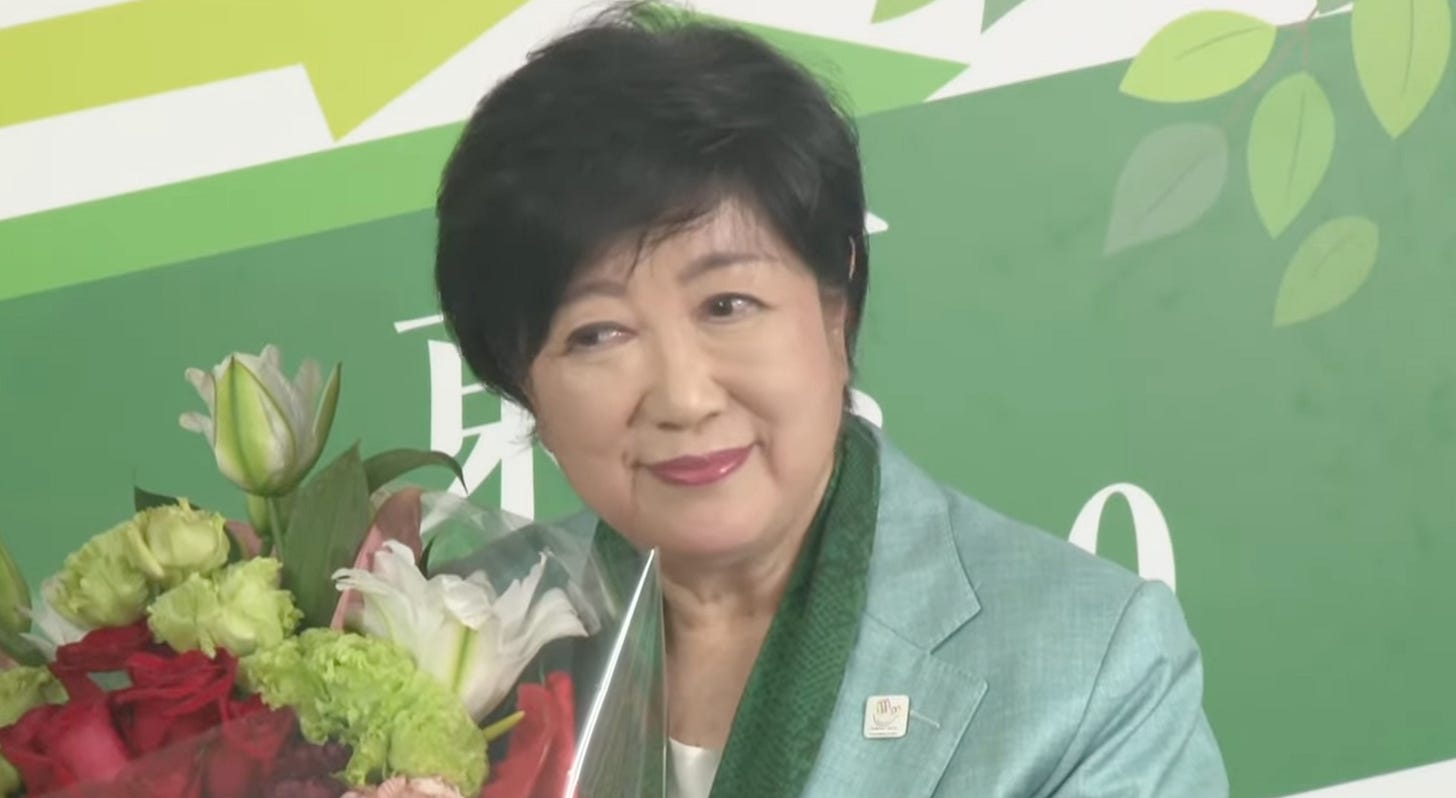

Despite the hype surrounding the matchup between Governor Koike Yuriko and Constitutional Democratic Party lawmaker Renhō, two of Japan’s leading female politicians, and the chaos surrounding the 56-candidate campaign for Tokyo’s governorship, in the end there was little drama. Koike won her third term with 43% of the vote. Renhō, meanwhile, not only did not win but fell to third, behind Ishimaru Shinji, the 41-year-old former mayor of Akitakata, a small town in Hiroshima prefecture. Ishimaru took 24.4% of the vote to 18.8%.

Koike wins handily

As the campaign unfolded, Koike’s victory increasingly appeared to be a foregone conclusion. Polls across the board suggested she had a comfortable lead, and she had locked up the support of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP); Kōmeitō; the Democratic Party for the People (DPFP), which brought along the support of the organized labor confederation Rengo’s Tokyo branch; and her own local Tokyoites First party.

According to exit polls, she not only was able to attract the bulk of voters from these parties, she also took significant shares of the independent vote. Asahi’s exit poll suggests that Koike received 32% of the unaffiliated vote, behind Ishimaru (36%) but well ahead of Renhō, who received only 16% of the unaffiliated vote. Kyodo News’s exit poll recorded similar figures. Meanwhile, a post-election online survey targeted at a random sample of Tokyoites conducted by Mainichi and the Social Survey Research Center suggests Koike won roughly 40% of independents, ahead of Ishimaru with roughly 30% and Renhō in the low 20s. Koike also made not-insignificant inroads into Renhō’s base, as the Asahi poll found that Renhō received only 72% of CDP supporters and 69% of Japanese Communist Party (JCP) voters.

Her victory may not look nearly as impressive on paper. She received more than 500,000 fewer votes than in 2020, even with turnout five percentage points higher. But both Renhō and Ishimaru were stronger candidates than she faced in 2020, suggesting that she won a robust mandate for a third term from a public that seems largely satisfied with her leadership.

With her reelection victory behind her, it is likely that speculation will again surface about Koike and her Tokyoites First party playing some kind of role in national politics. Her strength among independents suggest that she and her party could complicate the outlook for single-member constituencies in Tokyo if they were to field candidates in the next general election.

Who is this guy?

Ishimaru Shinji’s second-place finish may be the biggest story of the election. A foreign exchange analyst at MUFG Bank before running for Akitakata’s mayorship in 2020, Ishimaru ran for Tokyo’s governorship to raise awareness of Japan’s population crisis, highlighting the overconcentration in Tokyo and the death spiral in rural communities. Ishimaru saw this firsthand, as Akitakata – which, like many communities, is the product of a Heisei-era merger of several declining towns – saw its population decline more than 28% from 1980 (just before Ishimaru’s birth) until 2020 (when he was elected mayor). Ishimaru’s performance is particularly impressive because he ran without the formal support or endorsement of any established political party. Instead, Ishimaru relied on social media, including a very active YouTube channel, to distribute his stump speeches, seeking to generate excitement among Tokyo’s voters.

His surprising success points to a genuine hunger from voters for generational change in Japanese politics, particularly among young voters, who, exit polls show, were especially enthusiastic about Ishimaru’s candidacy. In other words, the public’s frustrations are not limited to the LDP and its scandals. Voters, particularly younger voters, are hungry for new faces and new ideas.

Whether Ishimaru himself becomes a political force remains to be seen. Ishimaru ran into trouble in Akitakata, where he sparred with town council members and was even sued for defamation for claiming on Twitter that a council member had fallen asleep and was snoring in a meeting, a case Ishimaru lost in the first instance and then lost again on appeal early this month. In its election on Sunday to pick Ishimaru’s successor, the town opted for a candidate promising a less confrontational style. Nevertheless, Ishimaru hinted on Sunday that he might run in the next general election, perhaps even in Hiroshima-1, Prime Minister Kishida Fumio’s district. He also did not rule out establishing a new party that could perhaps appeal to independents as Ishimaru did in Tokyo.

The path from a surprising second-place finish to building a movement is far from linear, and the general election field will be crowded. Nevertheless, Ishimaru will be a figure to watch.

Renhō’s loss

It is not difficult to understand how Renhō failed. She needed to mobilize independent voters on her behalf – and as seen above, both Koike and Ishimaru performed better with independents than Renhō. Her defeat will likely prompt another round of internal discussions of whether and how the CDP should coordinate with the JCP, which was criticized by Rengo and the DPFP during the campaign. She also leaned on CDP heavyweights Edano Yukio and Noda Yoshihiko during the campaign, suggesting that the CDP is still struggling with the public’s memories of Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) governments. To the extent that CDP leader Izumi Kenta distanced himself from Renhō’s candidacy – and Noda and Edano are the most frequently mentioned rivals to Izumi in the CDP’s September leadership election – Renhō’s defeat may help him make the case that the CDP cannot be over-reliant on DPJ veterans as it makes its own bid for change-hungry independents.

Bad day for the LDP

Even without a candidate in the gubernatorial race, it was a bad day for the LDP. The LDP may have backed Koike, but her victory hardly depended on the ruling party’s support. More importantly, of the eight candidates the party ran for Tokyo metropolitan assembly by-elections, only two were victorious (the LDP held five of the seats up for election before the vacancies). One of the defeats was in Hachioji, home of Hagiuda Kōichi, one of the Abe faction bosses implicated in the kickback scheme. It will be difficult for Kishida – and the would-be contenders for the LDP’s leadership – to look at Sunday’s results and not conclude that voters are increasingly hungry for political change.