Thank you for reading Observing Japan. This post is available to all readers.

If you are looking for timely, forward-looking analysis of the stories in Japans’s politics and policymaking that move markets, I have launched a new service through my business, Japan Foresight LLC. For more information about Japan Foresight’s services or for information on how to sign up for a trial or schedule a briefing, please visit our website or reach out to me.

I appeared on the Jacob Shapiro podcast this week, talking about some of the issues discussed in this post.

The Financial Times dropped a major story about the US-Japan relationship this afternoon, reporting that the Japanese government “scrapped” – the article’s word – a 2+2 meeting of foreign and defense ministers on 1 July after Elbridge Colby, under secretary of defense for policy, demanded that Japan raise its defense spending to 3.5% of GDP.

Demetri Sevastopulo and Leo Lewis write:

US secretary of state Marco Rubio and defence secretary Pete Hegseth were due to meet Japan’s defence minister Gen Nakatani and foreign minister Takeshi Iwaya in Washington on July 1 for annual security talks known as the “2+2”.

But Tokyo scrapped the meeting after the US asked Japan to boost defence spending to 3.5 per cent, higher than its earlier request of 3 per cent, according to three people familiar with the matter, including two officials in Tokyo.

I have previously written at length about Colby’s views of Japanese defense spending, and there is not much more to say on the matter, other than that if 3% was unrealistic, 3.5% is deeply unrealistic.

The constraints I wrote about last year – fiscal and administrative as well as political – are if anything even more salient, since subsequently the ruling coalition lost control of the House of Representatives, reducing Prime Minister Ishiba Shigeru to the head of a minority government. Meanwhile, the fiscal constraints have become even more salient, as rising interest rates have reignited fears about the sustainability of the Japanese government’s debt.1

Perhaps the most significant change since last year is that Japanese attitudes towards the United States – and the domestic politics of the US-Japan relationship – have changed since the start of the second Trump administration. Historically, ensuring that the bilateral relationship is on sound footing is one of the most important duties for Japan’s prime ministers. But since 2 April — if not since 20 January — the public’s mood has shifted. As remarks from lawmakers and journalists, Tokyo knows that it has entered a new era and it has to be willing to say no to the United States when it makes unreasonable demands.

The public is, if anything, even more eager for leaders to say no to the United States. Polls have repeatedly showed that the public overwhelmingly favors the government’s taking a harder line in trade talks with the United States, no doubt encouraging Ishiba to repeatedly emphasize that he is not rushing to complete a deal with Donald Trump if it means sacrificing Japan’s national interests.2 Meanwhile, in the Asahi Shimbun’s large poll conducted by mail for Constitution Day, only 24% said in relations with the United States Japan should follow the US as much as possible, compared with 68% who said that Japan should be as independent as possible. The same poll found that only 15% think that the US were truly defend Japan, while 77% do not. The public is not eager to abandon or be abandoned by the United States — only 16% approve of replacing the centrality of the US for Japanese foreign policy with a focus on cooperation with China and other Asian countries, with 66% opposed — and 62% approve (31% strongly, 31% somewhat) of increasing Japan’s defense capabilities. Rather, there appears to be opposition to a heavy-handed approach from Washington that, for example, demands that Japan raise defense spending to politically impossible levels or tolerate arbitrarily high tariffs on Japan’s exports to the United States.

As these data points suggest, the Trump administration’s approach on both trade and defense cooperation is needlessly provocative. Japan wants the United States engaged in the region and has been willing to bear a lot to make it possible. Its leaders want to raise defense spending, with the public’s understanding. The Japanese government, despite its dissatisfaction with the Trump administration’s tariffs, has negotiated in good faith and avoided threatening retaliation, even as it has been frustrated with its negotiating partner’s approach. All Japan’s leaders — and the public — appear to be asking for is for Japan to be treated as an ally, an ally that has been making increasingly important contributions to regional security, to say nothing of Japanese companies’ contributions to the US economy, instead of being treated like a vassal. In rejecting a 2+2 meeting with the US, a forum Tokyo treats with considerable reverence, the Ishiba government appears to be drawing a line against the treatment.

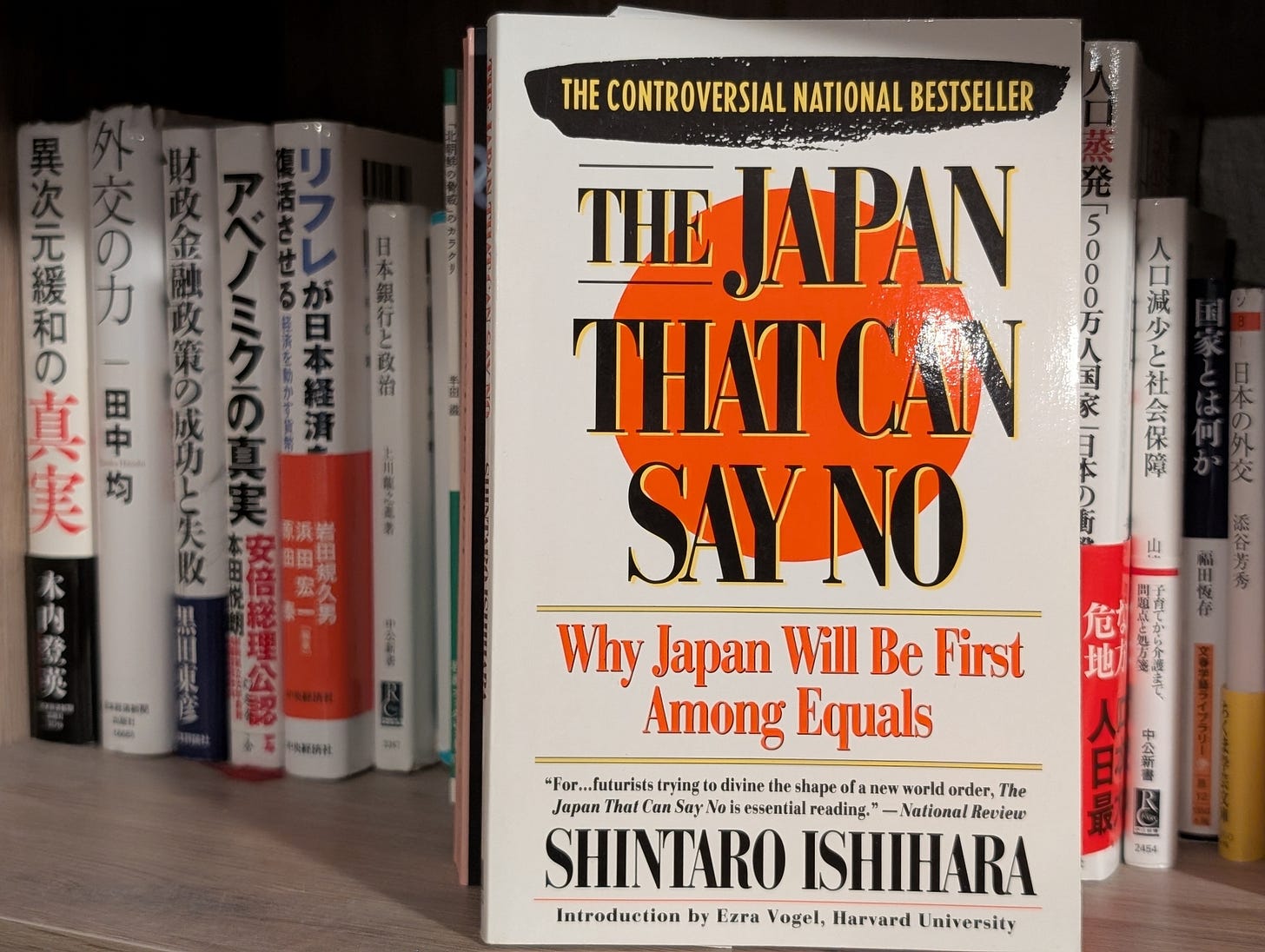

In 1989, not long after Donald Trump ran an ad in leading newspapers attacking Japan for free-riding on US defense guarantees — “America should stop paying to defend countries that can afford to defend themselves” — novelist, politician, and provocateur Ishihara Shintarō and Sony founder Morita Akio made waves on both sides of the Pacific with their book, The Japan That Can Say No. That book was a nationalist polemic written at the peak of Japan’s rise as an economic superpower, and did not end up serving as a blueprint for Japan’s foreign policy. Instead, the Japan that is ever so quietly saying no today is not petulantly or aggressively saying no. Rather, its leaders are trying to square outsized US demands with the real political and economic constraints of an era of relative decline.