Thank you for reading Observing Japan. This post is available to all readers.

If you are looking for timely, forward-looking analysis of the stories in Japans’s politics and policymaking that move markets, I have launched a new service through my business, Japan Foresight LLC. For more information about Japan Foresight’s services or for information on how to sign up for a trial or schedule a briefing, please visit our website or reach out to me.

This Week in Japanese Politics will be delivered to paid subscribers tomorrow.

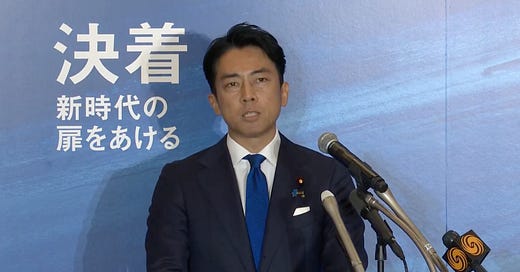

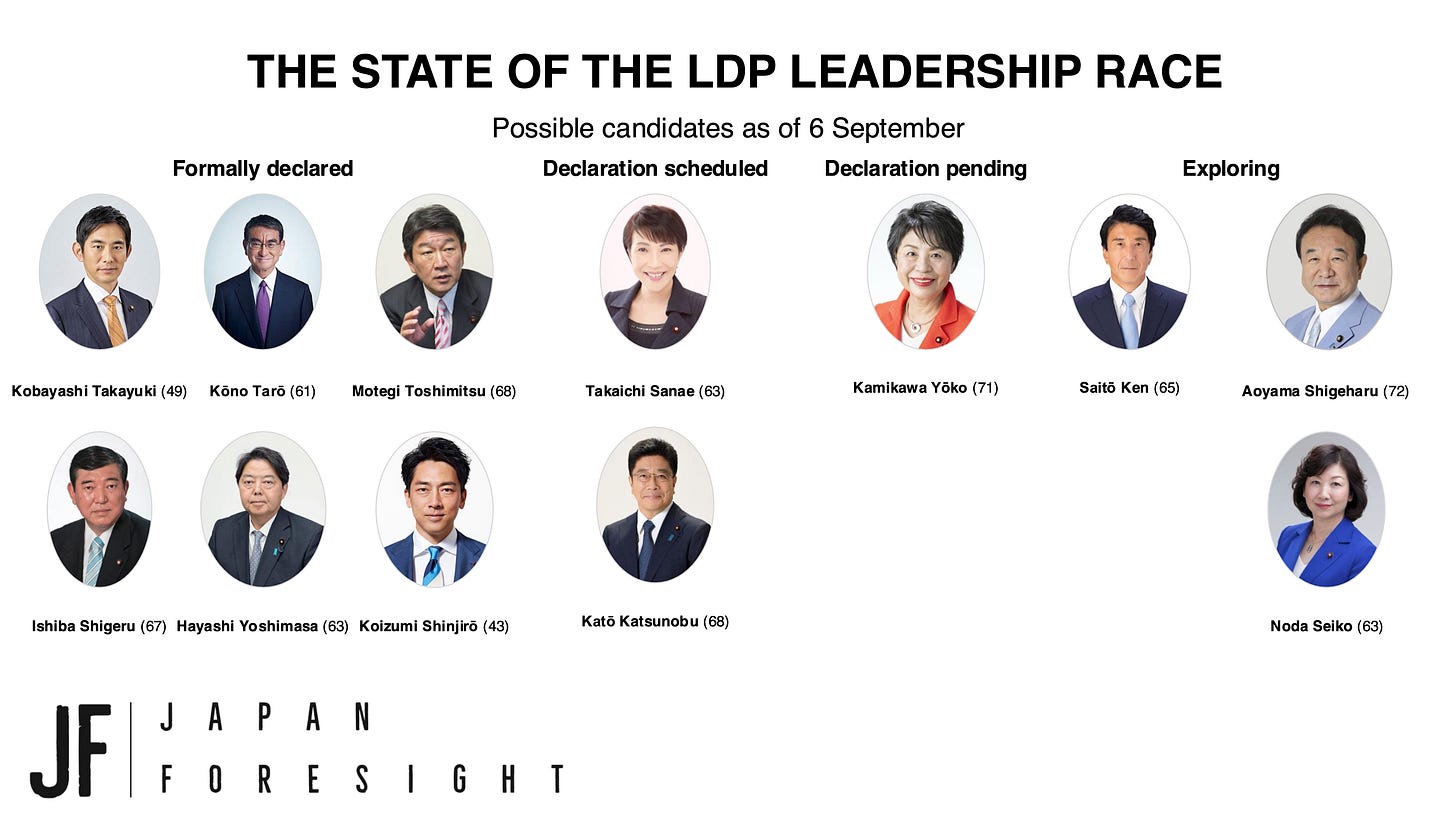

After some delay while Japan dealt with the impact of Typhoon No. 10, Koizumi Shinjirō (profiled here) finally held a press conference to announce his formal entry into the Liberal Democratic Party’s (LDP) leadership race. He is now the sixth candidate to join the race — officially making this the largest LDP field yet, with at least two or three more expected — and enters the field if not as a presumptive favorite than as the candidate with the best chance of advancing to the second round and winning the leadership altogether. In a crowded field, he will attract outsized media attention and, along with other candidates, has ramped up his social media activities as he seeks to build on his lead in the polls among rank-and-file LDP supporters.

In his press conference on Friday, 6 September, the forty-three-year-old Koizumi sought to demonstrate what makes him different from the other more seasoned candidates in the race. Speaking at a rapid clip – though carefully checking his notes in light of past criticism for careless speech – the younger Koizumi lamented Japan’s global economic decline; bemoaned the lingering influence of the “old LDP” as symbolized by the kickback scandal; and drew on memories of his father by deploying one of Koizumi Junichirō’s catchphrases, “reform without sanctuary.”1 While the younger Koizumi talked of policy priorities – economic reforms to encourage more flexible labor markets to benefit start-ups and small businesses, the need for additional political reform, perhaps even going so far as to withhold the party’s nomination from recalcitrant lawmakers, the urgency of constitutional revision, legislation to allow spouses to have separate surnames (“after thirty years of debate,” he noted) – it is clear that Koizumi will campaign less on a particular policy platform than on himself as a dynamic, disruptive agent of change, deploying his youthful vigor to get Japan moving again.

Everything about his press conference conveyed a sense of impatience, that Japan has no time to lose to make necessary reforms and that Koizumi is eager to get to work. He stated that there are three reforms he will deliver within one year – and preemptively dismissed those who will say that delivering these policies is impossible – including a bill allowing separate surnames, further political reforms including scrapping the opaque “policy activity funds,” and labor-market reforms to promote flexibility, encourage ride-sharing and other gig work, and scrap the “annual income wall” that imposes limits on part-time workers.2 He said, perhaps in another allusion to his father’s tenure, that he would be prepared to call a snap election quickly after becoming prime minister in order to win a mandate for these reforms.3 And he expressed impatience with the pace of constitutional revision, saying that it was time to ask the people directly whether to clarify the status of the Self-Defense Forces and add state of emergency provisions to the national charter.

Koizumi is not invulnerable. His more-experienced opponents will be quick to attack his lack of experience, particularly in foreign policy, about which he had fairly little to say in his press conference; in a field with at least three and possibly four foreign ministers and three former defense ministers, he is all but certain to face questions about his ability to lead Japan on the world stage. They will likely try to neutralize Koizumi’s pitch for generational change by asking whether this is the right moment for Japan to elect its youngest-ever prime minister. Koizumi tried to preempt these attacks Friday by arguing that he will assemble a strong team that will “get things done,” but he will undoubtedly continue to face these questions.

But they will not necessarily doom his candidacy either. As Ishiba Shigeru, who has more to lose than most from Koizumi’s candidacy, said of the press conference, “It felt fresh and vigorous. I have known Mr. Koizumi since before he was elected, and he is exactly as I envisioned at that time.” Voters have signaled in election after election and poll after poll that they are deeply frustrated by the LDP and the state of Japan’s democracy more broadly. Both LDP voters and independents, presented with a dramatically younger alternative who is promising to move quickly to get things done, may find a Koizumi-led LDP invigorating in a way that no other candidate can match. For a party whose leaders were not too long ago warning that the LDP faced a crisis worse than in 2009 – when the party was driven into opposition – the prospect of Koizumi delivering electoral victories that recently seemed unthinkable may be too difficult to pass up, even if it could mean having to reckon later with a young, impatient leader determined to upend entrenched interests and drag the LDP into the future.

He also, like his father, referred to “reform” repeatedly, using the word 改革 kaikaku 56 times in just over an hour.

He presented these changes as intended to maximize individual choice and create a more pluralistic society, a theme he has addressed before.

With the new prime minister likely to be confirmed by the Diet on 1 October, the likeliest dates for a snap election are 27 October — the first possible date given that the previous Sunday would be only 19 days after the prime minister’s selection and the same date as an upper house by-election in Iwate — or 10 November.