Thank you for reading Observing Japan. This post is available to all readers.

If you are looking for timely, forward-looking analysis of the stories in Japan’s politics and policymaking that move markets, I have launched a new service through my business, Japan Foresight LLC. For more information about Japan Foresight’s services or for information on how to sign up for a trial or schedule a briefing, please visit our website or reach out to me.

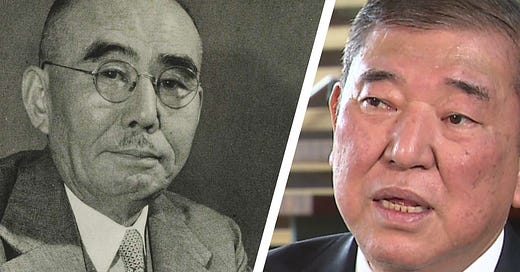

In his policy speech to open the autumn extraordinary session of the Diet, Prime Minister Ishiba Shigeru prompted some commentary when he prominently featured two quotes from Ishibashi Tanzan, a leading liberal thinker of the twentieth century and short-lived postwar prime minister.

“I will always be mindful of the eternal destiny of the nation, and I will endeavor to debate and set the direction of national policy solely with a mind toward the welfare of the entire nation, without being partial towards sectional interests or the opinions of a segment of the people,” he said, quoting Ishibashi’s policy speech.

As I noted in my review of the book he published before the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) leadership election last year, Ishiba is an open admirer of Ishibashi, including his articulation of a “small Japan” foreign policy (which Ishibashi articulated in response to Japan’s prewar continental expansionism).

Although he did not explicitly cite Ishibashi’s foreign policy thinking in November, Ishiba’s invocation of Ishibashi did not escape attention – see articles in Nikkei, Mainichi, Yomiuri, and Jiji – as a reminder of one of the major influences on his thinking. And as Ishiba and Japan face the challenges of the second Trump administration, the intellectual legacy of Ishibashi Tanzan could loom ever larger as the government navigates a swiftly changing international order.

I could not help but think of Ishiba and his admiration of Ishibashi when I saw what Takaichi Sanae, his rival for the LDP’s leadership, said in a discussion on Fuji TV Wednesday evening.

Takaichi pushed back against criticism of Donald Trump’s “America First” rhetoric, arguing that “it’s natural” for an American leader to say this. “As a Diet member, I too am thinking of ‘Japan First.’ It is natural to maximize the interests of the people of one’s own country,” she said. She went on to offer defense of various Trump administration policies, before offering her own prescriptions for Japanese policies.

Her defense of “America First” is facile – America First does not just mean putting the interests of Americans first, but rather reconceptualizing US national interests so that only Americans (and, in fact, only some Americans) matter when thinking about the role of the United States in the world – but setting that aside, her appearance is useful for clarifying the choice that Japan faces in the coming years.

The choice, in fact, is remarkably similar to the choice it faced between the world wars, when Ishibashi articulated his “small Japan” vision. Ishibashi, watching Japan become drawn inexorably into war and imperialism on the Asian continent, argued for free trade and respecting national self-determination and against military intervention and annexation. As Sharon Nolte, author of the definitive English-language biography of Ishibashi notes, Ishibashi was not necessarily making a moral argument against imperialism but a pragmatic argument; he thought Japan’s interests – its security and prosperity – were better served by liberalism than by imperialism.

Japan’s leaders thought differently. As S.C.M. Paine writes, “Japanese leaders had compelling reasons to intervene in China. Capitalism was down for the count. Communism was anathema. Diplomacy was ineffective. Playing by the rules established by the Western powers promised economic disaster, while disregarding the rules risked war and isolation. Uninvited, the Imperial Japanese Army stepped in to the rescue.”1 Richard Overy, in Blood and Ruins, notes how economic nationalism in the liberal powers after the start of the Great Depression helped push Japan and others in the direction of imperialism. “The world’s strongest economies might have played a role in protecting the system they had long profited from, but they chose not to, at the expense of the rest,” he writes.2 This does not exonerate Japan’s leaders from the choices they made but it does suggest that Ishibashi’s arguments faced significant obstacles to their being embraced.

It is not difficult to see the echoes in the present day. Japan has, since 1945, become thoroughly embedded in a liberal world order and in many respects the “small Japan” envisioned by Ishibashi has prevailed, though the Yoshida Doctrine was not entirely to Ishibashi’s liking, as he wanted Japan to be a truly independent trading nation – including trade with the Soviet Union and People’s Republic of China – and rejected the US-Japan security treaty.3 Over time, Japan has become not only a beneficiary of this order but one of its most ardent defenders, indeed, as Mireya Solis argues, one of its leaders. It is impossible to read Japan’s 2022 national security strategy without seeing the degree to which the Japanese government recognizes that its national interests – the security and prosperity of the Japanese people, first and foremost – have depended on the maintenance of an international order that categorically rejected the legitimacy of territorial conquest and the advancement of rules to promote international economic openness and integration, the absence of both of which helped push interwar Japan towards imperialism.

Trump’s “America First” foreign policy is a fundamental rejection of the norms and institutions that have enabled smaller powers – Japan included – to survive and thrive. As Nikkei’s Akita Hiroyuki writes, “Trump sees the world as a jungle governed by power, not ethics or rules.” Faced with this challenge, Japan’s leaders face a fateful choice between defending an international order that the United States is prepared to abandon or deciding that the spirit of the age is every nation for itself and acting accordingly.

It was apparent at the time that the contest between Ishiba and Takaichi was a battle for the soul of the LDP, but now it increasingly appears that it may well be a contest for the soul of Japan itself, between Ishiba’s neo-“small Japanism” – in which Japan takes more responsibility for its own defense while pursuing a more balanced, independent foreign policy that seeks to preserve a liberal global order favorable to Japan’s mercantile interests – and Takaichi’s national greatness conservatism, in which Japan, instead of relying of international institutions and international partners, turns inward and takes steps to maximize its power and guarantee its security on its own. It is noteworthy that later in the Fuji TV program in which she defended “America First,” she also argued that Japan needs to take immediate and drastic measures to become self-sufficient in food and energy. As I wrote about Takaichi’s candidacy in September, she launched her campaign calling for the “protection of Japan’s vital interests and for policies to maximize Japan’s comprehensive national power,” and, as she said Wednesday, “if there were an election today, my campaign promises would be entirely the same.”

This debate is still in its early stages, as Japan grapples with the meaning of Trump’s return. But, as the editorial pages of Japan’s major dailies showed this week, the terms of the debate are becoming increasingly clear.4 If the United States is prepared to abandon an international order that Japan has recognized as vital not only to its interests but to its conception of itself as a global power, it will have to decide whether to do what it can to preserve that order by its own devices — though not by itself — or whether it needs to reconsider its interests and indeed its identity and alter its behavior accordingly, i.e. meet the challenge of America First by turning to Japan First. Of course, both choices would require significant changes in how Japan engages with the world, overturning the habits of more than seventy years of foreign policy. Naturally, Japan’s first choice is not to have to make a choice at all, to find some way of salvaging a status quo that appears increasingly endangered. As long as the hopes of pursuing a double hedge strategy remain, this debate will remain at a relatively low boil. But this debate over Japan’s path in the twenty-first century has begun, and Japanese leaders and the public may have to grapple with their choices sooner than they may have thought.

S.C.M. Paine, The Wars for Asia, 1911-1949, p. 272. Richard Overy makes a similar argument in Blood and Ruins, as did Abe Shinzō in his 2015 statement on the seventieth anniversary of the end of World War II. “Japan gradually transformed itself into a challenger to the new international order that the international community sought to establish after tremendous sacrifices,” he said.

Richard Overy, Blood and Ruins. p. 27.

See Sharon Nolte, Liberalism in Modern Japan, p. 331. Richard Samuels also identifies Ishibashi “Small Japanism” as an antecedent for what he calls postwar “mercantile realism.” See Securing Japan, p. 128.