The Idealist

Ishiba Shigeru and the deep roots of conflict in Japanese politics

Thank you for reading Observing Japan. This post is available to all readers.

If you are looking for timely, forward-looking analysis of the stories in Japan’s politics and policymaking that move markets, I have launched a new service through my business, Japan Foresight LLC. For more information about Japan Foresight’s services or for information on how to sign up for a trial or schedule a briefing, please visit our website or reach out to me.

In his classic book Japan: The Intellectual Foundations of Modern Japanese Politics, the late Tetsuo Najita posited that much of Japan’s modern political history can be explained by the interaction – and tension – between two major intellectual tendencies, what he called “bureaucratism” and “idealism.” The former is the ideology of national power. “It is a ‘mission’ (shimei) to enhance the well-being of the nation through the systematic creation of industrial wealth,” he writes. It is flexible, pragmatic, and elite-driven in its pursuit of national power and prosperity. The latter is more amorphous, but Najita characterizes it as driven by a sense of obligation to others, a sense of “humaneness,” and the pursuit of a deeper spiritual satisfaction – and often mobilizes in reaction to the overreaching projects of bureaucratism.

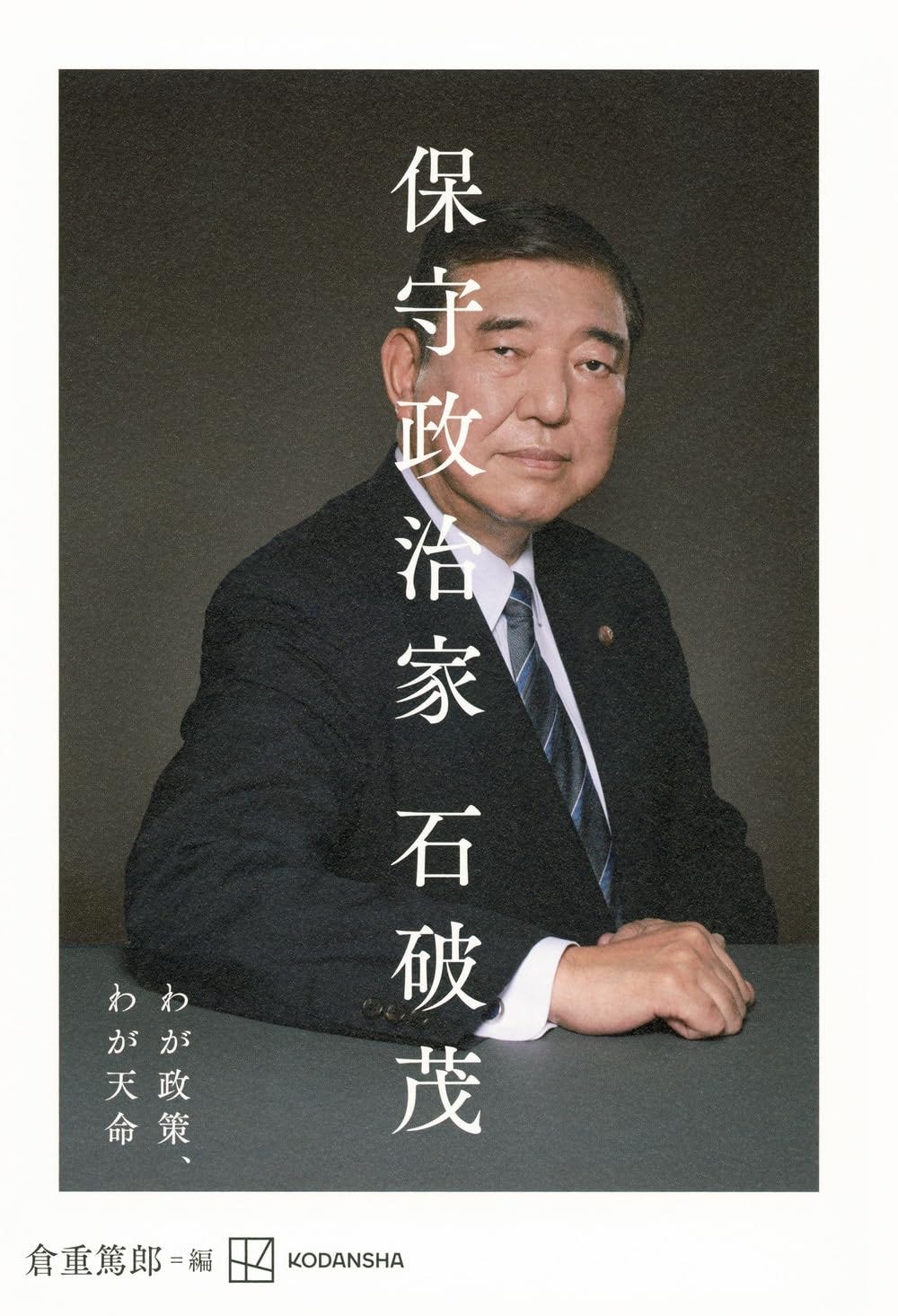

When reading Ishiba Shigeru’s new book – Conservative Politician: My Policies, My Destiny [保守政治家 わが政策、わが天命] – I could not help but think how comfortably Ishiba fits in this framework for thinking about Japanese politics. Ishiba is often called a “policy wonk.” He has, of course, referred to himself in the past as a “defense otaku,” the rare Japanese politician whose interest in defense policy verged on an obsession. But in this deeply personal account of his political history, Ishiba shows that what sets him apart from his colleagues in the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) is not that he is a policy wonk. It is that he is an idealist in a party that has become increasingly wedded to bureaucratism. This tension is at the heart of his conflict with the late Abe Shinzō, who was the direct heir to a conservative political tradition that prioritized the pursuit of national wealth and power, frequently referring to his “mission” to use state power to mobilize the nation to overcome challenges.

Ishiba is not only explicitly critical of “Abe politics,” he repeatedly shows that on the most fundamental issues facing Japan, he is a political idealist, wanting “purer” solutions that will not only “solve” problems but will make Japan and the Japanese people better. I think Ishiba’s idealism is precisely why it is often difficult to make sense of his politics, which does not fit comfortably into a liberal-conservative dichotomy. Indeed, Ishiba himself occasionally refers to himself in this book as a “conservative liberal.” This book therefore provides invaluable insight into the mind of the man who could well be Japan’s next prime minister.

—

In a companion essay appended to the end of the book, Kurashige Atsuro, a member of the editorial board of the Mainichi Shimbun, refers to Ishiba’s “father complex.” But he is not only driven by his attachment to his natural father, Ishiba Jirō (1908-1981), a construction ministry official, long-serving Tottori governor, and upper house LDP lawmaker whose career culminated in service as home affairs minister shortly before his death. He is also deeply attached to the late Tanaka Kakuei (1918-1993), who was political patron to both the elder and younger Ishiba. The elder Ishiba apparently said, “I would die for Tanaka,” while the younger Ishiba was told to enter politics by Tanaka even though his father told him not to become a politician.1

Ishiba’s attachment to Tanaka – who is perhaps best known outside Japan as the “shadow shogun” laid low by the Lockheed scandal but who was beloved by many Japanese as the “commoners’ prime minister” – may well be the key to understanding Ishiba’s political commitments. Tanaka, who rose from an impoverished upbringing in Niigata prefecture to become Japan’s most powerful politician, is often considered the paradigmatic corrupt LDP politician, a master mobilizer of money in politics who institutionalized the LDP’s structural corruption. But he was deeply idealistic, committed to ensuring that rural backwaters like Niigata were not left behind by Japan’s postwar economic miracle, the essence of his plan to “remodel the Japanese archipelago” by stitching together the country with new shinkansen lines, highways, and bridges that would also promote development in poorer areas. Politics, Tanaka said, is people’s livelihoods.2 In much the same way that urban machines in US politics practiced democracy through the delivery of benefits to their constituents, so too was the Tanaka machine geared at distributing the fruits of prosperity to constituents across Japan.3

Ishiba inherited from Tanaka a commitment to the practice of democratic politics. It is the job of politicians to get out and talk to their constituents. “The number of votes yielded is nothing more than the number of houses walked. The number of votes yielded is nothing more than the number of hands shaken,” he said.4 Ishiba notes that when he was first campaigned for the House of Representatives in 1986, he would visit 200 or 300 houses a day, ultimately visiting 54,000 houses and receiving 56,534 votes. “I probably would have never become a Diet member if I had not been taught [by Tanaka], ‘the starting point of politics is to always be in contact with voters, and to directly take up the voices of the people.’”5

Of course, by the time Ishiba entered politics, Tanaka and his faction were in decline, as Tanaka battled the Lockheed scandal, ill health, and the defection of much of his faction to his lieutenant Takeshita Noboru’s new faction.6 But Ishiba, like Ozawa, was part of a wave of younger Tanaka followers who wanted to preserve what was best about Tanaka-ism – its idealistic concern for ordinary people – and deliver a new, cleaner style of politics. As a first-term Diet member, he was involved in the “Utopia Political Research Association” led by Takemura Masayoshi, which systematically studied the role of money in politics as the Recruit scandal roiled the LDP. He eventually left the LDP with Ozawa and other lawmakers in 1993 to join the Japan Renewal Party and later the New Frontier Party (NFP) as part of this commitment to a new politics, though he returned to the LDP when he wearied of infighting in the Ozawa-led NFP.

This ethos continues to animate Ishiba’s political worldview. He wants an honest, clean politics that delivers results for the public, that is honest with the people about what needs to be done, and is thoroughly democratic. While the Tanaka “school” dominated the LDP for close to a quarter century – and deserves to be considered its own tradition alongside the Yoshida school and the Kishi line – it fell out of favor due to the corruption scandals of the late 1980s and early 1990s, the defections in 1993 and thereafter, and, after the end of the Cold War, the revival of the Kishi line via the rise of Abe Shinzō and his allies.7 After a quarter century of dominance by Abe, which includes Kishida’s tenure seeing as how he embraced Abe’s politics, it is almost jarring to encounter Ishiba’s politics.8

He fundamentally rejects how Abe ruled. He describes how Abe governed through friend-enemy distinctions, identifying his enemies and mobilizing his friends to attack them. He dealt kindly with friends, but harshly with foes. He was also, Ishiba says, an ideologue who thought he had all of the answers. Ishiba, however, says that this is not conservatism but rather a reactionary rightism. Conservatism, he argues, is a disposition, not an ideology, a desire to control the pace of change and preserve things of value from the past.9 As part of this disposition, he is deeply committed to democracy. “Politicians…respect their opponents, and if they see a mistake, they correct it. They respect minority opinions and politely answer questions from the opposition in the Diet. This is the way to be a conservative,” he writes.10 The contrast with Abe, who was eager to correct his opponents to the point that as prime minister he was chastised for heckling questioners in the Diet, is apparent. Ishiba also is critical about Abe’s dishonesty when questioned about the Moritomo and Kake Gakuen scandals, as well as the cherry-blossom viewing festival scandal, in the Diet. Finally, far from rejoicing at the weakness of the political opposition, Ishiba is dismayed, saying that a weak opposition makes the LDP weaker and discourages grassroots participation.11 A robust opposition, he says, is necessary for holding the government accountable, a role, he adds, that the LDP played superbly when it was in opposition from 2009 to 2012.12

This earnest commitment to “democratic localism” also animates Ishiba’s critique of Abenomics, which he says used monetary easing and fiscal stimulus to stimulate the economy – weakening the yen and boosting the profits of Japan’s biggest corporations – but ultimately failing to overcome deflation, boost productivity, or otherwise improve the livelihoods of workers and poorer regions, which he believes is a source of latent strength in Japan’s economy. “Please look at Japan’s history,” he writes. “There is not a single example of the metropolises changing the country. It is always the people of the countryside who change the country.”13 He is also bitter that his criticisms of Abenomics led his LDP colleagues to attack him for betraying Abe, instead of welcoming the opportunity for discussion and debate about the best course of action. He is therefore determined to unwind Abenomics and build a more equitable economy — with greater redistribution via corporate and wealth taxation — that creates new opportunities for parts of Japan that have been left behind. Ishiba’s way of thinking and talking about economic policy is different from many of the other candidates and his colleagues in the LDP because he is first and foremost focused on ensuring the prosperity of all Japanese – including his constituents in rural Tottori, on the coast of the Sea of Japan – not just the big cities and big businesses.

Ishiba’s intellectual inheritance from Tanaka also extends to foreign policy and national security, the areas in which Ishiba is widely acknowledged as one of the foremost experts in the LDP. But despite his expertise, he is also not necessarily a “hawk” in the sense that Abe and his allies have been national security hawks. Ishiba explains that he and other younger members of the Tanaka school inherited a hostility to war from their patron, who after his experience as a conscript in Manchuria was thoroughly opposed to rearmament as a politician and also resistant to being overly dependent on the United States as it prosecuted the Cold War.

It may be here where Ishiba’s views are most out of the mainstream of the contemporary LDP. In contrast to Abe, and now, Takaichi Sanae, Ishiba is thoroughly opposed to the pursuit of power and national greatness for their own sake. He approvingly cites Ishibashi Tanzan’s “Small Japan Policy,” saying that it teaches that while Japan should have the military strength to maintain a military balance with China in the East and South China Seas, the bilateral relationship with China “cannot just consist of the military balance.”14 Japan must learn from Ishibashi, he says, and pursue win-win diplomacy with Beijing. At the same time, however, Ishiba’s discomfort with Abe’s pursuit of great power status – as Abe said in Washington in 2013, “Japan is not, and will never be, a tier-two country” – also leads to a certain discomfort with the United States, which he believes simultaneously encourages this type of foreign policy in Japan while also subordinating Japan’s independence. He is also uncomfortable with the predominance of the “China threat” theory within Japan, arguing that it is possible to acknowledge security threats and seek to strengthen deterrence while continuously seeking opportunities to reduce tensions and bolster cooperation with China. He praises the long line of LDP politicians who have acted as “pipelines” to China’s leaders, and laments that if politicians try to pursue similar relations with Beijing today, they are attacked as “China lovers.”15 He urges humility in Japan’s approach to its history as part of an effort to build trust with its Asian neighbors.

To be sure, he is not naïve about Japan’s security environment. But, he writes, “as a democratic nation, major policy changes and budget shifts require broad public understanding.” He wants Japan’s leaders to be frank about the risks Japan faces and honest about what is required, including both the amount of money needed to strengthen Japan’s armed forces and how to pay for these larger defense outlays. He wants the Japanese people and their representatives to be more mature and sophisticated in thinking about Japan’s security challenges and how to meet them, an argument he has made in previous writings.

As part of his hope for Japan to be more responsible for its own security, he thinks that Japan’s relationship with the United States needs to change fundamentally. Indeed, his uneasiness about Japan’s relationship with the United States probably sets him apart from his LDP colleagues more than any other issue. He writes, “I believe that Japan is still not a truly independent country. The essence of the US-Japan Security Treaty is its asymmetry. The US is obligated to defend Japan, and Japan is obligated to host US forces in its territory…which country that allows foreign troops to be stationed on its territory as an obligation is an independent country?”16 He is not opposed to the US-Japan alliance or even to the stationing of US forces in Japan, recognizing them as “necessary” for Japan’s defense. But as his repeated call for revising the Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) governing US forces in Japan suggests, he is determined to reduce asymmetries in the relationship. He thinks that there needs to be much greater – and more mutual – consultations, including, he notes, how nuclear weapons should be used to deter threats.

In this sense, he is critical of how Prime Minister Kishida Fumio has handled national security policy, suggesting that instead of a more fundamental debate about what is necessary for Japan’s national security, he focused the debate on a target for defense spending of two percent of GDP – in line with NATO standards – whether this target is appropriate for Japan’s needs.17 He instead wants the government to focus on passing a national security basic law that would spell out Japan’s obligations and capabilities and enable it to act as a full partner in the US-Japan relationship (as well as in the “Asian NATO” that Ishiba has placed at the center of his campaign), an approach that would ask more from the public but would also be more honest.

—

It is therefore clear that if Ishiba were to win the LDP’s leadership and Japan’s premiership, it would signify a rejection of a quarter century of dominance by Abe and his national greatness conservatives, the triumph of a style of politics that has been pushed to the margins of the LDP for most of Ishiba’s career. Perhaps for that reason it is still difficult to believe that Ishiba, despite his popularity with the LDP’s rank-and-file voters, will be able to prevail in his fifth bid for the LDP presidency. He is not just asking his parliamentary colleagues to vote for him. He is asking them to reject Abe politics thoroughly and decisively, to embrace a more idealistic way of governing Japan and to question the assumptions that have guided LDP leaders for most of the post-Cold War era. Ishiba’s earnest and idealistic politics may be too great a departure for his party to accept.

Readers of Ivan Morris’s The Nobility of Failure know that Japan’s idealists rarely succeed in their struggles to create a purer, more humane Japan. As Morris writes:

There is another type of hero in the complex Japanese tradition, a man whose career usually belongs to a period of unrest and warfare and represents the very antithesis of an ethos of accomplishment. He is the man whose single-minded sincerity will not allow him to make the maneuvers and compromises that are so often needed for mundane success. During the early years his courage and verve may propel him rapidly upwards, but he is wedded to the losing side and will ineluctably be cast down. Flinging himself after his painful destiny, he defies the dictates of convention and common sense, until eventually he is worsted by his enemy, the "successful survivor," who by his ruthlessly realistic politics manages to impose a new, more stable order on the world.

Ishiba himself seems to recognize that he may well be playing this role in Japan’s political drama. He launched his campaign by stating that this will be his “last battle,” with victory far from assured. He knows that his idealism – his determination to serve the public and remind his colleagues of their obligations to voters – has cost him the support of his parliamentary colleagues, who resent his questioning. And even if he were to prevail in his fifth bid for the leadership, it is unlikely that he would have an easy time managing an LDP far from united behind his idealistic vision for how Japan should be governed. His destiny may well be tragic, win or lose, an increasingly isolated idealist in a party committed to the pursuit of power and prosperity at all costs. But he is also a singular figure in Japanese politics, and students of Japan’s political system are fortunate that he wrote this characteristically earnest, forthright account of his political life.

P. 52; p. 60.

A belief that has lived on in his acolyte Ozawa Ichirō’s slogan, “livelihoods first.”

Jacob Schlesinger makes this comparison in his Shadow Shoguns, still the indispensable English-language account of Tanaka and his machine. [P. 107]

Ishiba cites this line on p. 167.

P. 77.

On the Lockheed scandal, Ishiba says his father believed that Tanaka was innocent, and that he believes his father. He also gestures towards a conspiracy theory – promulgated by journalist Tahara Soichirō and others – that the Lockheed scandal was retaliation by the United States for Tanaka’s assertion of independence on relations with China, the Arab world, and other issues, though he admits, “I have not heard any concrete facts unearthed that reinforce this theory.”

This story, of course, is a major thread of my book on Abe, The Iconoclast.

In a similar vein, in his own writings Ozawa Ichirō has cited the famous line from Lampedeusa’s The Leopard, “If we want things to stay as they are, things will have to change.”

P. 153.

P. 46.

He even notes his respect for the Japanese Communist Party, despite obvious disagreements, on p. 165.

P. 176.

It is partly through Ishibashi’s influence that Ishiba refers to himself as a “conservative liberal.”

P. 186.

P. 89.

P. 30-31.