Between past and future

The meaning of what Takaichi, Noda, and Saitō said in their final night rallies

Thank you for reading Observing Japan. This post is available to all readers.

If you are looking for timely, forward-looking analysis of the stories in Japans’s politics and policymaking that move markets, I have launched a service through my business, Japan Foresight LLC. For 2026, I am preparing a new pricing tier for public institutions. For more information about Japan Foresight’s services or for information on how to sign up for a trial or schedule a briefing, please visit our website or reach out to me.

My firm Japan Foresight published a Japan Risks 2026 report and I am offering it to Observing Japan readers for a discount. Paid subscribers can click here for information on how to purchase. Free subscribers can find information here.

I was quoted in the Financial Times’s “The Big Read” on the general election, “Can Sanae Takaichi govern Japan on star power alone?”

Paid subscribers can join a realtime starting shortly before polls close at 8pm JST Sunday.

Japan’s general election campaign ended on Saturday with major party leaders holding competing rallies across Tokyo.

This has by any definition been a strange campaign. It was unexpected; it was the shortest-ever general election; its coming spurred the unlikely creation of a new party from former rivals; and what looked like an extraordinary gamble by a prime minister may be about to pay off in a huge way. It was also a general election campaign that did not seem to be about much more than whether Prime Minister Takaichi Sanae should remain in office.

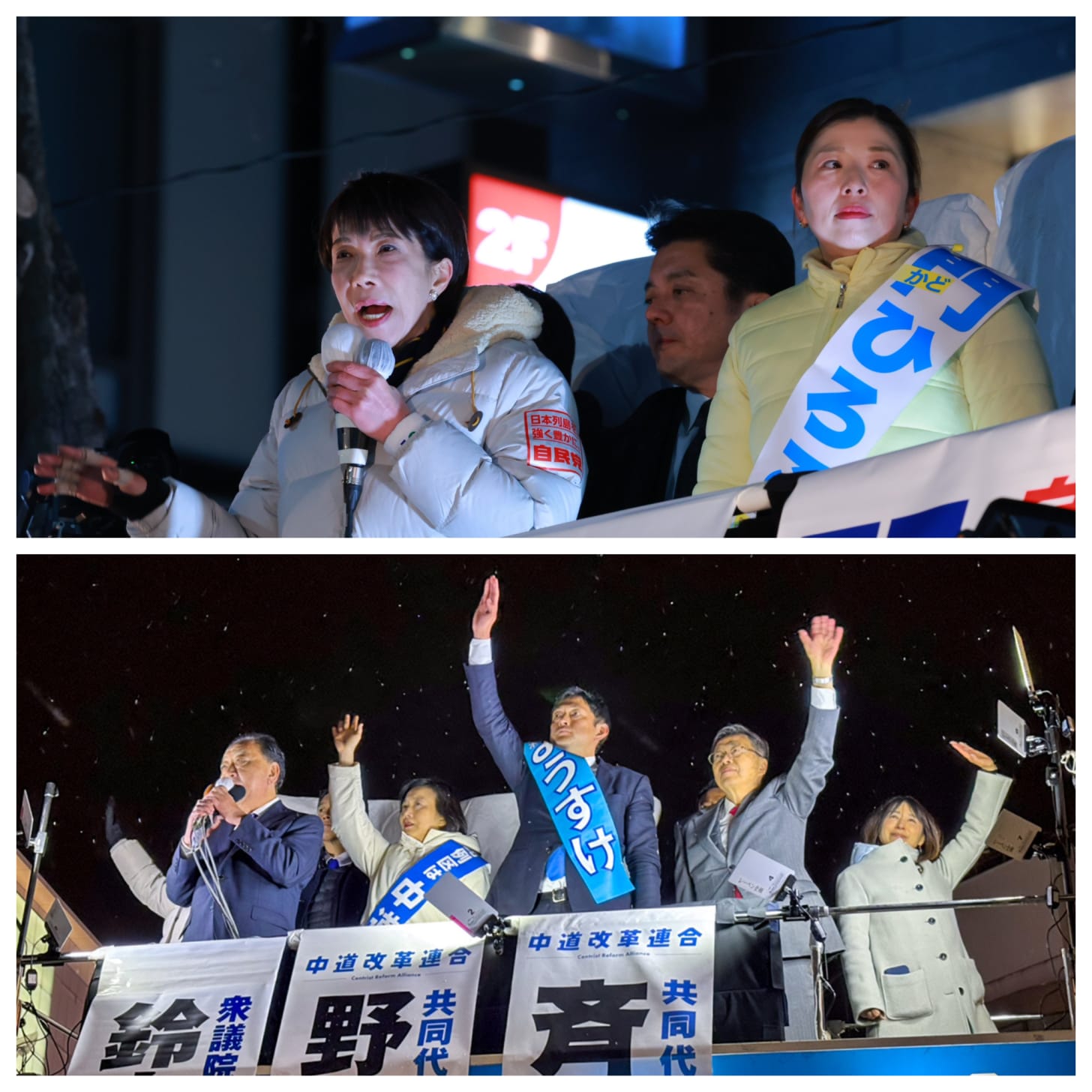

However, in the remarks by party leaders Saturday night, it does seem clear that voters have been presented with not competing policy visions but rather competing ideas for Japan’s democracy and how to advance the country’s interests in the face of a troubling future. The differences between Takaichi and Centrist Reform Alliance (CRA) co-leaders Noda Yoshihiko and Saitō Tetsuo were especially stark.

Takaichi ended the campaign in Tokyo’s Setagaya ward, campaigning for the Liberal Democratic Party’s (LDP) Kado Hiroko in the Tokyo eighth district.

Her final night stump speech was similar to virtually all of her other campaign stump speeches. She is not talking about specific policies – the much-debated consumption tax cut, for example – but a more comprehensive vision for the country. Indeed, Takaichi, not unlike her political mentor Abe Shinzō, is refreshingly frank about her vision for Japan. She spends most of her speech talking about the need to raise investment in the interest of promoting national autonomy and self-reliance. While we can debate whether this is an inward turn or a “recalibration”, her message is, to borrow the words used by one of her advisers in a different context, “in the end we can only rely on ourselves.”1

Once you appreciate this about Takaichi, everything else falls into place, including her view of politics, which again is drawn from the post-cold war “new conservatism” that Abe, Takaichi, and others articulated beginning the 1990s. As I wrote in The Iconoclast:

The new conservatives foregrounded the strength of arms, impatience with deliberative democracy, and strong leadership, believing the state’s leaders should be free to act as required to safeguard national survival, regardless of prevailing ideological or political commitments.

She is, in short, asking the Japanese people for a mandate so she can do what it takes to ensure Japan’s security and prosperity. Her desire for political stability is a desire to make the opposition irrelevant, to limit its opportunities to ask questions or challenge her vision for the country. It is perhaps not a coincidence that the scandal of the campaign was Takaichi bowing out of a leaders’ debate on NHK, citing health reasons even though she did not cancel her campaign rallies the same day.2 Similarly, she displayed a certain prickliness towards criticism at a campaign rally on Thursday, when she referred to “those who want to destroy” her, referring to academics and other experts questioning her fiscal policies in particular. This is, as Noda Yoshihiko suggested in an impassioned plea to voters he posted on his blog earlier this week, the revival of “Abe politics.” The belief that electoral majorities are a license to rule without restraint (an “elective dictatorship” model of parliamentary democracy); the impatience with critics and opponents (recall that Abe was disciplined for heckling opposition lawmakers during parliamentary debates); and the supreme confidence that she has the answers to Japan’s’ problems. In a sense, she is another avatar of the dream of the Heisei political reformers, strong leadership solving national problems.

Across town, in Ikebukuro, Noda and his Centrist Reform Alliance (CRA) co-leader Saitō Tetsuo were offering a dramatically different vision for politics. Perhaps what is most notably is that whereas Takaichi did not refer to the CRA or its leaders at all, the CRA leaders used their remarks to single out Takaichi and her style of leadership for criticism. They repeatedly referred to her pursuit of policies that will divide the country, contrasting with their desire to pursue a politics that reconciles conflicting opinions in order to pursue the happiness of the people. Noda mocked her pledge to “work and work and work and work,” saying that under the LDP people “work and work and work and work” without seeing their wages rise. He referred to an incident in which an LDP candidate suggested that the people might have to shed blood for Japan, suggesting that this mood is “spreading within the LDP.”

However, what is ultimately most striking about both Saitō and Noda’s remarks is how backwards looking they are. They both repeatedly refer to Japan as a “peace-loving nation” (平和国家), referring to the postwar legacy surrounding Article 9 of the constitution. They warn of the dangers of Japan being drawn into war under Takaichi. They defend the three non-nuclear principles and warn that with a large majority Takaichi will pursue constitution revision and “full spectrum” collective self-defense. Noda uses a portion of his remarks to discuss how policies pursued by the Koizumi and second Abe administrations made Japanese society more unequal. They both talked about Takaichi’s LDP moving to the right. But for many voters this rhetoric falls on deaf ears. It's political rhetoric for people who still get home newspaper delivery.

The references to left, right, and center, the allusions to governments that are increasingly ancient history for younger voters (the youngest voters this year were born after the first Abe administration), the invocation of terms like “peace-loving nation”: one begins to understand why the CRA’s support among young voters is abysmally low. There are few concessions to the reality of the significant gaps between how older and younger voters think about politics, presenting what is still the main opposition party as out of touch with many voters.

To some extent, this is just another clash between “idealism” and “bureaucratism” as outlined by political historian Tetsuo Najita, not unlike the clash between Ishiba Shigeru – who also criticized “Abe politics” and called for a more inclusive form of democracy – and Abe and Takaichi (as I discussed here). But there is also a clash between past and future. Whatever the flaws in Takaichi’s program – at the very least she is running some extraordinary risks in her game of chicken with financial markets – she is fixed firmly on the challenges and opportunities of today. Indeed, unlike Abe, who often was obsessed with relitigating old fights between left and right and undoing historical wrongs (e.g. a constitution written by foreign hands), Takaichi is laser focused on more practical concerns. If there is a lesson from this campaign, it is that her politics will not be defeated through old slogans or appeals to old ideological battles that young voters do not themselves remember. Nor will she be defeated with warnings about what cannot or should not be done. To be sure, this does not mean that she is not rooted in Japan’s conservative traditions, particularly the most statist strands of conservatism. But she is not fixated on or trapped by labels, which undoubtedly helps broaden her appeal. As Takaichi and other leaders before her have understood, there is something to be said for forthrightly describing the country’s challenges and offer something in response, using clear and simple language.

Ultimately, I do not know what Japan’s next successful opposition party will look like, but I have a feeling it will neither look nor sound like what the CRA was offering on Saturday night.

Further reading

Despite bad weather in much of the country appearing to reduce early voting in some prefectures – though not in Yamagata, which has led the country in turnout in six straight elections – early voting overall still rose by 26.56% relative to 2024.

The various seat targets the ruling and opposition parties are aiming for Sunday.

Nikkei explains how some races are called as soon as the polls close.

Dr. Nakamats runs again.

Stats on the distances covered by party leaders during the campaign. Takaichi led with a total of 12,480 kilometers covered.

Incidentally, this is why some observers are completely misunderstanding her intentions towards fiscal policy. She is not interested in fiscal expansion as an end in itself: she is interested in fiscal policy as a means to achieving these ambitions. This is not Abenomics 2.0.

Subsequent reporting has suggested that her cancellation was discussed within the government several days ahead of time.