Thank you for reading Observing Japan. This post is available to all subscribers.

If you are looking for timely, forward-looking analysis of the stories in Japans’s politics and policymaking that move markets, I have launched a new service through my business, Japan Foresight LLC. For more information about Japan Foresight’s services or for information on how to sign up for a trial or schedule a briefing, please visit our website or reach out to me.

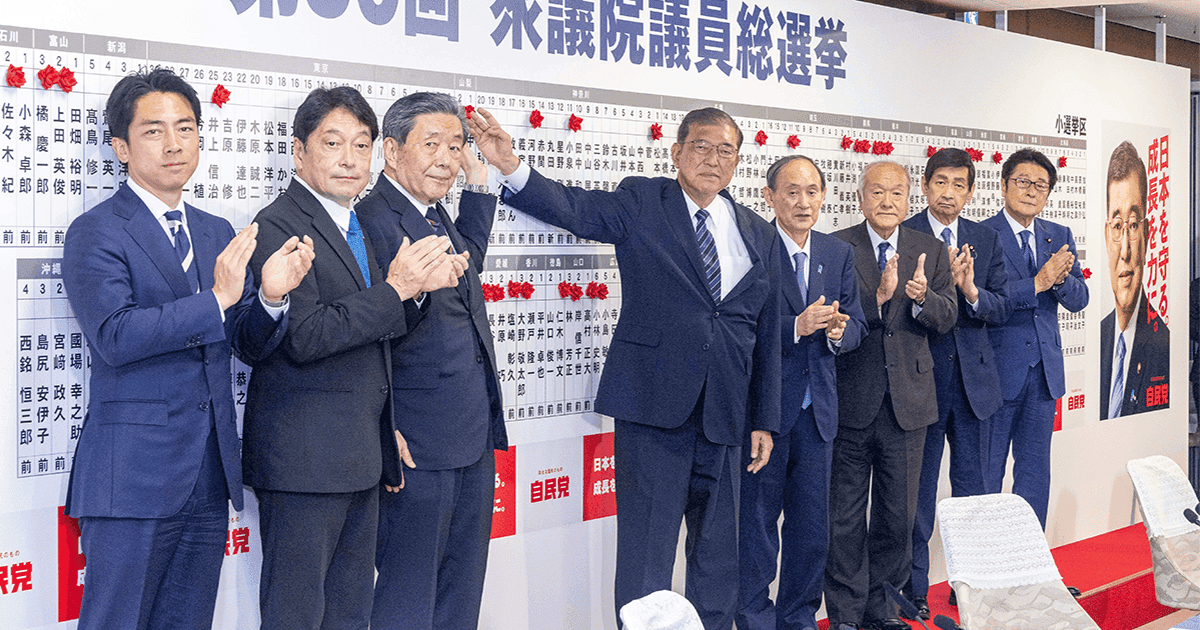

The day after the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and Kōmeitō fell eighteen seats short of a majority in the House of Representatives, the constellation of power in Nagatachō is being reconfigured. The actors who will make decisions about the budgets, laws, and policies that will govern Japan are already shifting.

Start with Ishiba himself, who appeared visibly diminished as it became apparent that the ruling coalition would lose its majority. For decades, Japan’s prime ministers – particularly its LDP prime ministers – have enjoyed ever-increasing power, controlling an ever-larger central government apparatus with officials answering directly to the prime minister and his closest advisers, greater control of personnel decisions at the highest levels of the government, and, within the LDP, a greater ability to set the policy agenda, regardless of the sentiments of backbenchers. Now, although Ishiba is determined to stay on, it appears that he could end up governing as a prime minister without the most basic source of power for a prime minister in a parliamentary system, a stable working majority in the legislature. If, as Ishiba’s mentor Tanaka Kakuei said, numbers are power, Ishiba simply does not have the numbers. Assuming that he prevails in the vote to select the next prime minister – more likely than not but not guaranteed – without a majority his ability to control the agenda, to pass legislation, and to move an agenda forward is diluted, even if he still has all the formal powers of the premiership. The most immediate consequence, therefore, is that Ishiba is already in a power-sharing arrangement.

Of course, Ishiba has to share power with his party, whose confidence in his leadership will be indispensable for his survival. He has already faced some calls for his resignation from prefectural chapters (Chiba and Yamaguchi), on the principle that in the wake of a calamitous defeat, it is appropriate for the party leader to take responsibility and resign, not just the party’s election strategy chief. But the calls have not only come from prefectural chapters. Lawmakers connected to the anti-Ishiba right wing of the party have similarly suggested that perhaps it would also be appropriate for Ishiba to also resign. But in this case, the numbers may be in Ishiba’s favor.

As diminished as the prime minister is, his adversaries in the party may be more diminished. The number of ex-Abe faction members in the House of Representatives was more than halved, dropping from fifty-four to twenty-two, while the Asō faction lost nearly a quarter of its lower house members, dropping from forty to thirty-one. (That said, the ex-Kishida faction, more sympathetic to Ishiba, lost eight members, nearly a quarter of its thirty-four pre-election lower house members.) Only four of ten scandal-implicated candidates who ran without the LDP’s nomination – counting Sekō Hiroshige, banished from the LDP altogether, in this group – won their seats. Twenty of the thirty-four candidates running without the safety net of a spot on the LDP’s PR lists were defeated. As enfeebled as this wing of the party is, its power is even more diminished considering that political reform will occupy a central place on the agenda in the coming months. Ishiba and his allies can credibly argue that the electoral defeat is not Ishiba’s fault but the ex-Abe faction’s. Meanwhile, Ishiba has another source of power over his rivals within the LDP: time. With government and ruling party officials looking to convene a special session of the Diet that will select the prime minister on 11 November, it will be difficult if not impossible for anti-Ishiba movement to unseat Ishiba as party leader in less than two weeks if he himself will not quit voluntarily. It could take an extraordinary effort to dispossess Ishiba that may be beyond the power of the anti-Ishiba bloc.

But within the ruling coalition, Kōmeitō may be the most diminished of all. The general election was a complete disaster for the LDP’s coalition partner. Not only did the party lose eight seats, one of the constituency races it lost was Saitama-14, where new party leader Ishii Keiichi was seeking to move from a PR seat to a constituency seat. Ishii, like other senior ruling coalition leaders, was running without being simultaneously included on Kōmeitō’s PR list, and is now out of the Diet entirely, leaving his party to seek a new leader for the second time in as many months after not changing leaders for fifteen years. But the most important number indicating Kōmeitō’s loss of power is not its twenty-four seats but the 5.96 million votes the party received in PR voting, its lowest total since the new electoral system was introduced in 1996 and the latest sign that the party’s electoral machine may be irreversible decline. Kōmeitō is still valuable to Ishiba and the LDP, not least because by renewing their coalition agreement, they have foreclosed one possible if unlikely option for the Constitutional Democratic Party to assemble a non-LDP coalition. But after decades of wielding a critical veto within the ruling coalition – acting as a “brake” on more extreme LDP ideas – its leverage as part of a minority government is diminished when other parties outside government could provide the decisive votes to pass legislation.

Indeed, the most important players in the new constellation of power are the Democratic Party for the People (DPFP) and Ishin no Kai, two parties whose support will be essential for the LDP to manage the legislative process.

Ishiba and the LDP will first and foremost be sharing power with Tamaki Yūichirō, whose Democratic Party for the People (DPFP) not only quadrupled its seats to 28 – and increased its gross vote total by nearly 250% compared with 2021 – but performed so strongly that the party had to yield three proportional representation seats (PR) it had won but ran out of PR candidates to fill them. As a technocratic, moderate conservative, Tamaki could be a suitable coalition partner for Ishiba – and the LDP would presumably rather have the DPFP as a formal coalition partner as a costlier form of commitment – but Tamaki has already demonstrated his power by signaling that he will not be joining an LDP-led coalition. Instead, he told Yoshino Tomoko, president of the labor federation Rengo, whose support was indispensable to the DPFP’s success (particularly in Aichi, where all four of its candidates won), that the party will cooperate with the LDP and Kōmeitō when their policies are good and will oppose them when their policies are bad. The ability to say no, to withhold something of value to Ishiba, is a power in its own right and Tamaki looks ready to use it.

Baba Nobuyuki, parliamentary leader of Ishin no Kai, should also have a stake in the post-election power-sharing arrangement, except that Baba too is grappling with the fallout from an election in which his party’s numbers were not what he had hoped for. Although Ishin impressively swept Osaka’s nineteen single-member districts, despite concerns that its support in its electoral stronghold was fading, the party lost six seats overall and received almost three million fewer votes than in 2021. This electoral performance is a problem not only because these figures are absolutely lower than in 2021, but because Baba was determined to make this general election the occasion for Ishin’s emergence as a truly national party that would unseat the Constitutional Democratic Party (CDP) as the leading opposition party. In short, while Baba could have a seat at the table as the leader of a thirty-eight-member parliamentary party, the deep dissatisfaction with his leadership from Ishin backbenchers (and from party founder Hashimoto Toru) could mean that Baba may have a harder time staying in his post than Ishiba – and it also makes Baba a weaker player than might otherwise seem the case as he faces call to step down. If, after all, he does not enjoy the full confidence of his backbenchers, his ability to bargain with the LDP, whether for a full or partial coalition agreement (though Baba has ruled out the former as well), is highly limited. In this case, Baba’s power might be less than even his numbers suggest.

Noda Yoshihiko and his Constitutional Democratic Party similarly may be less powerful than they would appear. The CDP gained the most seats in absolute terms, picking up fifty seats to a total of 148, solidifying its position as the leading opposition party. The LDP-led government will have little choice but to include Noda and his party in consultations, since House of Representatives will give them greater voice in parliamentary committees, and its parliamentary strength could give greater weight to a threat to call a no-confidence motion.

But Noda’s power may also be less than the raw seat total would suggest. First, in absolute terms, the CDP’s gross vote total barely increased from 2021 to 2024. The CDP’s gains were due less to a massive surge in voter support than to a better distribution of the party’s votes (and the precipitous decline in Ishin’s and the Japanese Communist Party’s votes), ensuring its victory in close races. It exploited dissatisfaction with the LDP, including among LDP supporters, but did not necessarily mobilize voters to a greater extent than before. This should, therefore, give the CDP pause if it were to try to use a no-confidence motion to force another snap election. Second, the CDP too will have to work with the DPFP and Ishin to press the government on political reform and other issues, and it may not be any easier for Noda to cooperate with these parties than for Ishiba, starting with the vote to select the next prime minister.

While the structure of power in the Diet is taking shape, what is less clear is how these actors will make decisions. The familiar process of the government’s drawing up policies, in consultation with the ruling parties, and then submitting policies to the Diet as legislation, will not work nearly as smoothly when other parties outside the government have to be included in consultations and when the government does not fully control all of the committees. The process will be slower, more opaque, and less decisive than has been the case for the past twelve years, as the bureaucracy has already recognized. Indeed, in the absence of clear political authority, the bureaucracy may find itself wielding more power than has been the case under LDP-Kōmeitō governments over the past twelve years.

Japan is unmistakably in a new era, as politicians and parties and bureaucrats adapt to a system in which power is more diffuse than it has been in years, in which decisions will be harder to reach and harder to implement, and in which abrupt shifts to the distribution of power may be the new normal.