This post is free for all readers. If you enjoyed this post and would like to read others — including my “This Week in Japanese Politics” feature that is published every Friday — please subscribe below.

In January 2023, Prime Minister Kishida Fumio visited Washington and delivered an address at the School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS) at Johns Hopkins University. That speech – which he called “Japan's decisions at history's turning point" – contained some blunt language for his American hosts, particularly on trade and economic cooperation. To that point, I called my essay on that visit to Washington, “A Japan That Can Speak Its Mind.”

On 11 April 2024, Kishida again came to Washington and he once again spoke his mind to a very different American audience, a joint meeting of both houses of the US Congress. The message he delivered was similar to that of his speech at SAIS and on other occasions.

As before, he spoke of the world’s being at “history’s turning point,” at which the postwar international order is “facing new challenges, challenges from those with values and principles very different from ours.” He explicitly addressed what he called the “undercurrent of self-doubt among some Americans about what your role in the world should be” – but repeatedly argued that, as he said, “the world needs the United States to continue playing this pivotal role in the affairs of nations.” He outlined the many global challenges facing Japan, the US, and other likeminded countries today, and did not shy away from making the link between Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and East Asian security, using another of his favorite lines: “Ukraine of today may be East Asia of tomorrow.”

Perhaps most importantly, he argued strongly that Japan is doing its part alongside the United States, quietly arguing against the Trumpian idea of free-riding allies taking advantage of the United States. He said:

I am here to say that Japan is already standing shoulder to shoulder with the United States.

You are not alone.

We are with you.

He rightfully pointed to the work his government has done to upgrade Japan’s defense capabilities, including raising defense spending (mention of which received a robust standing ovation); joining with the US and others to sanction Russia; providing assistance to Ukraine; and forging a new set of partnerships with other democracies across Asia.

—

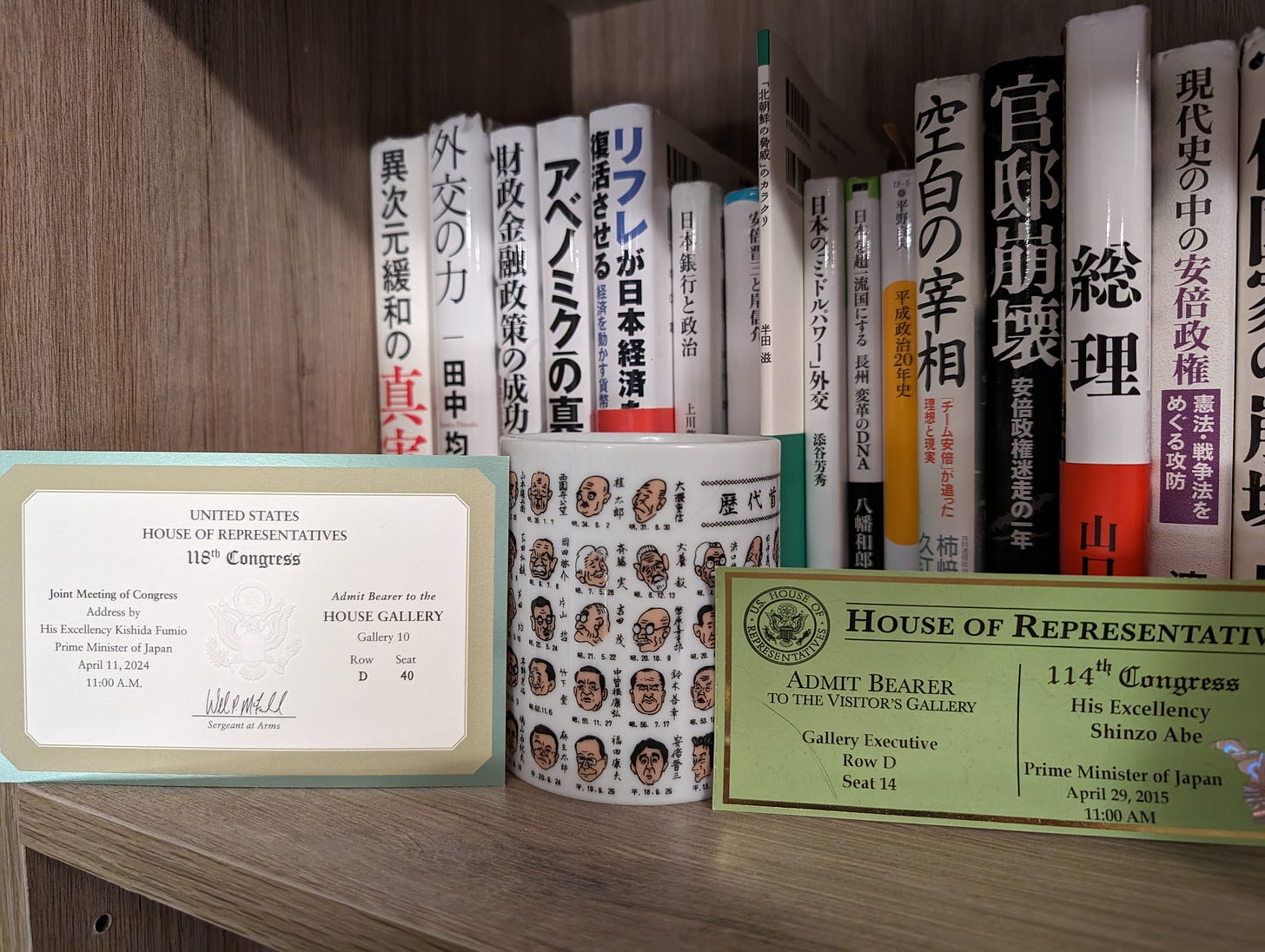

This is the second time I have been able to attend a Japanese prime minister’s speech to a joint meeting of Congress. There were significant differences between both the men and the moments.

Abe’s address in 2015 felt like more of a spectacle. The first address to a joint meeting by a Japanese prime minister, it also felt like a chapter in Abe’s redemption story. Not only had he returned to the premiership, he also came bearing a message of historical reconciliation to a legislative body with which he had been embroiled in a fight over historical memory only eight years prior. The House galleries were completely packed for Abe’s speech; I don’t recall seeing a single empty seat.

The mood for Kishida’s speech today was different. There were empty seats in the galleries. Arriving in the chamber, it did not feel like a historic occasion in the way that Abe’s felt like in 2015. The vibes, as they say, were different. But then, Kishida is a different messenger than Abe. If Abe came bearing personal and historical baggage – and, by 2015, a growing global reputation – Kishida is still a bit of a mystery, less of a history, less of a global personality.

But the most significant difference was the substance of the message. Both prime ministers may have spoken fondly of time spent in the United States when they were young, but in important ways the similarities stopped there.

Abe’s speech reads as a message from a more innocent historical moment, which, in retrospect, it may well have been. Trump had not yet taken his escalator ride; the US was still negotiating the Trans-Pacific Partnership; Britain was still in the European Union; the full scale of Xi’s ambitions were still unfolding; the Covid-19 pandemic was five years in the future.

Kishida is addressing a dramatically different world, in which world order is fracturing and in which the United States is straining under the burden of global leadership. The world simply looks more dangerous, particularly for liberal democracies.1 It was striking that after a series of rousing ovations during the introduction to Kishida’s speech, the room was noticeably quiet when Kishida acknowledged American self-doubt while stressing the urgency of American leadership at this inflection point. Members of Congress were clearly studying the copies of the speech more closely as he pivoted to this appeal. Both Abe and Kishida were determined to keep the US committed to regional and global leadership. But Kishida’s appeal for US leadership came with greater urgency, reflecting the scale of the challenges it faces at home and abroad. And, to be sure, it reflected how Japan has changed thanks to the policies of both Abe and Kishida.

--

From the start of Kishida’s premiership in 2021, I have tried to figure out what exactly Kishida wants. What did it mean for the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) to have a leader and for Japan to have a prime minister who characterized himself as liberal and dovish? Why did Kishida want to be prime minister and what did he hope to achieve with power?

I think with this speech we can see that Kishida has in fact found a calling. Particularly since Russia invaded Ukraine, he has been especially clear-sighted about the challenges to a rules-based international order, how those challenges threaten Japan’s national interests, and what Japan needs to do to guarantee peace and prosperity in the future. “I am an idealist but a realist, too,” he said. “The defense of freedom, democracy and the rule of law is the national interest of Japan.”

It has often been assumed that Kishida’s dovish reputation has enabled him to deliver policies – higher defense spending and the acquisition of counterstrike capabilities – that eluded the more hawkish Abe. There may well be truth to this, but I think it is also the case that Kishida has shown himself to be more of a realist than Abe was.

Abe’s ambitions were as much emotional as logical. He wanted to lift restraints imposed on Japan at the end of the Second World War, he wanted Japan to be a great power and to be ambitious. Abe was certainly capable of practicing realpolitik and became better at it over time, but his vision of Japan and its place in the world was laden with historical baggage. For Kishida, matters are simpler. He has perceived threats to the Japanese people and has worked methodically to address those threats. And in doing so, he has not just finished work that Abe left unfinished – he has drafted his own map for guiding Japan through uncharted waters.

--

So Kishida came to Washington and spoke his mind. It was a strong speech, well delivered – his delivery was more fluent and fluid than Abe’s – and I expect after this Washington’s estimation of him will rise, which could be useful if he survives to win a second term as LDP president in September. But I am also not convinced that Kishida’s speech, or the state visit more broadly, will fundamentally improve his situation at home.

Still, it is clear after this state visit that Kishida and his government have not only perceived the contours of the new era more clearly than many, but have already left an important mark on how Japan will navigate a more challenging world.

It makes sense that the vibes were different. Abe was the Frank Sinatra of Japanese PMs, a charming crooner with a hint of a bad boy aura. Kishida is, I still think, Charlie Brown, with many a Lucy in the LDP snatching the football away. But that’s okay. He’s a good match for Biden – a bland and stodgy but competent and principled manager. Joe and Fumio are similar in that sense. They tend to do the right things but get no respect. After this shindig, they’ll go back to face poor approval ratings and rants from their respective citizens about how everyone is paying $100/¥15,000 a day on groceries. Will Joe and Fumio still have jobs this December? Hope you can share your insight into this vexing question, Mr. Harris.

Abe’s real talent was in the way he handled Donald Trump. Maybe the “personal baggage” element helped – game recognizes game. It was weirdly fascinating to watch Abe get into the good graces of Trump with hamburgers and golf and sumo, of all things. This is something Kishida probably wouldn’t be good at. Which begs the question, who would be a good PM candidate for managing the Don in his second term? Maybe Shinjiro Koizumi, who could put Trump at ease with his youthful and fawning “aw-shucks” attitude. I can see Koizumi Jr. becoming pals with Don Jr. Then there’s Taro Aso, who likely won’t be PM but is a great Trump whisperer nonetheless. Aso went to see Trump recently, and I can imagine them swapping stories about how yakuza/mobster figures approach them, tears streaming out of their eyes, begging, “Sir, sir, can I have your fedora/MAGA cap?”