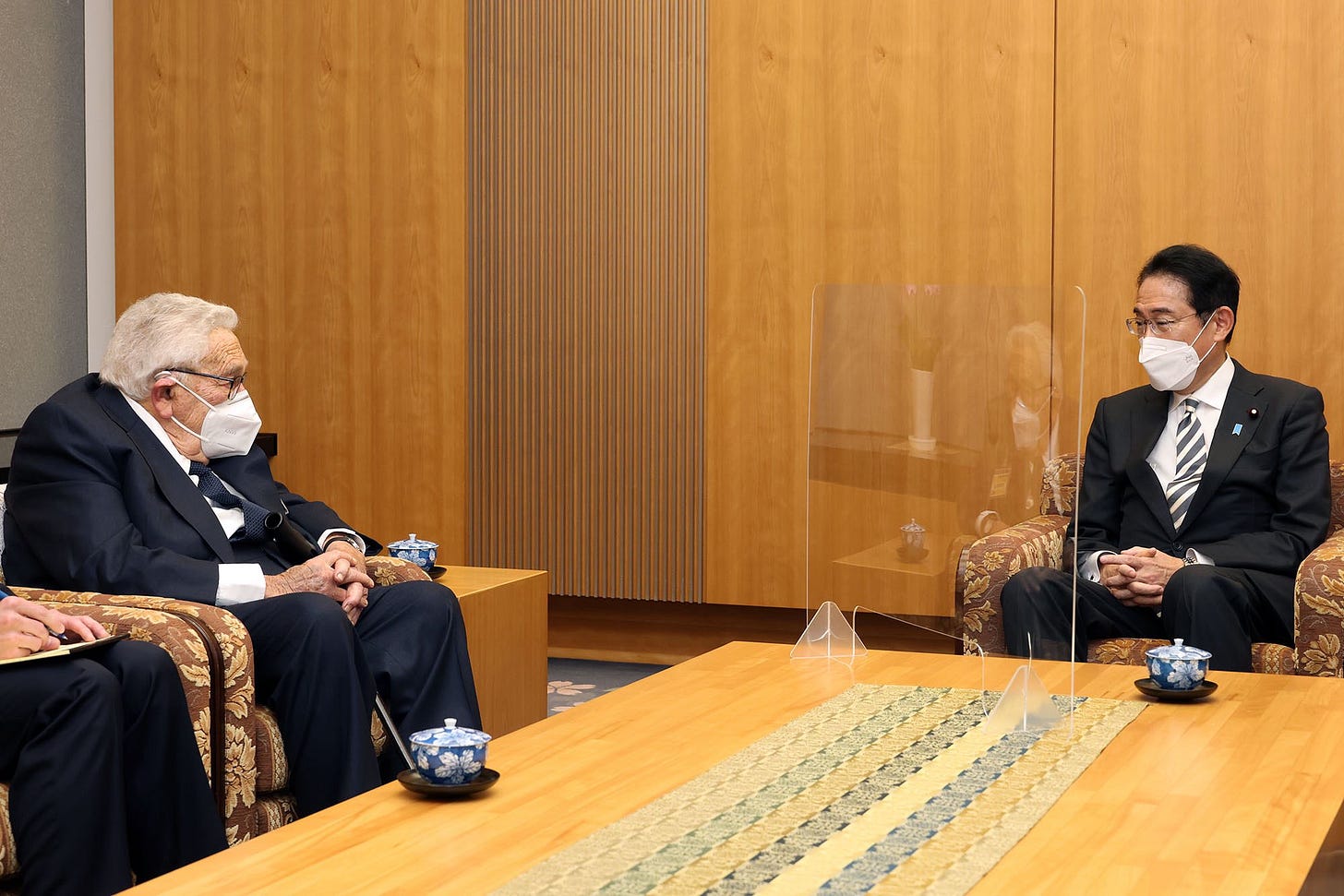

Following the death of Henry Kissinger, national security adviser and secretary of state under Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford, on 29 November at 100, Prime Minister Kishida Fumio delivered a brief message to Kissinger’s widow, Nancy:

I was deeply saddened to hear the passing of your husband, Dr. Henry Kissinger, former Secretary of State of the United States of America. Dr. Kissinger dedicated his life to peace and stability in the international community over the decades. In his relations with my country, he played a critical role in the reversion of Okinawa to Japan. His vision for a world without nuclear weapons has been highly respected here as well as in the world.

I myself have had the opportunity to meet him in person many times since I was young, and have received much insight from him. His great footsteps cannot be understated. I extend my sincere condolences to you and your family as well as the U.S. government and the American people.

The mention of Kissinger’s work late in life as part of the Global Zero movement to abolish nuclear weapons perhaps explains why Kishida in particular would feel compelled to deliver this statement, given his own commitment to ridding the world of nuclear weapons.1

But it is a little unusual too. For example, when George Shultz, secretary of state from 1982 to 1989 under Ronald Reagan (who also supported the Global Zero movement), passed away at 100 on 6 February 2021, the Japanese government’s response was muted. In a press conference several days following Shultz’s death, then-Foreign Minister Motegi Toshimitsu offered a brief appreciation for Shultz’s service at the end of the cold war and his work in strengthening US-Japan relationship during and after his tenure at the State Department. Perhaps if Abe Shinzō had still been prime minister he would have offered a prime ministerial statement to honor the secretary of state who had worked closely with his father during his tenure as foreign minister, but his successor, Suga Yoshihide, did not.

Leaving aside the question of whether Kissinger’s role – to borrow the words that the National Security Archive at George Washington University used for its documentary record of Kissinger’s activities – in “Secret Bombing Campaigns in Cambodia, Illegal Domestic Spying, Support for Dictators, and Dirty Wars Abroad” merits this manner of statement from a Japanese prime minister, Kissinger’s record as a steward of the bilateral relationship while in office would hardly seem to merit a prime ministerial statement. Indeed, it is revealing that the only mention of Kissinger’s place in US-Japan relations was in Okinawa reversion, which was hardly an unambiguous triumph.2 In that sense, Kishida’s statement is revealing as much for what it does not say.3

There is, frankly, little sense that Kissinger ever accorded Japan – or perhaps more precisely, Japan as it is – much significance in his thinking. “During his first three years in office…Kissinger paid little attention to America’s allies in Western Europe and even less to Japan,” writes John Stoessinger, carefully, in a friendly biography of Kissinger published in 1976. Others have described Kissinger’s approach to Japan less charitably. Seymour Hersh, in The Price of Power, quoted Kissinger saying of Japan, “The Japanese are mean and treacherous but they are not organically anti-American; they pursue their own interest…It is essential for the U.S. to maintain a balance of power out there. If it shifts, Japan could be a big problem.” The historian Michael Schaller, meanwhile, characterized Kissinger’s views of Japan as follows:

Kissinger shared Nixon's views on Okinawa, but did not see Japan as critical to U.S. security. He found Japanese diplomats difficult to relate to, complaining that they were ‘not conceptual,’ lacked long-term vision, and made ‘decisions by consensus.’ They were, he mocked, ‘little Sony salesman’ [sic]. Chinese leaders such as Zhou Enlai fascinated Kissinger, but Japanese officials seemed ‘prosaic, obtuse, unworthy of his sustained attention.’ Worst of all, Kissinger complained, ‘every time the Japanese ambassador has me to lunch he serves Wiener schnitzel.’4

Why was Japan a blind spot for Kissinger?

First, as Schaller and others have noted, Kissinger was not a particularly avid student of international economics. As C. Fred Bergsten, who had the unenviable task of advising Kissinger on international economic affairs at the National Security Council from 1969-1971, wrote in a December 1973 essay in the New York Times, “Henry Kissinger's record on economics is dismal. On most issues, he has totally abstained.” Among his missteps, Bergsten notes, was “[botching] the textile negotiations with Japan, which badly soured US-Japan relations, on several occasions.” It is perhaps understandable that postwar Japan, whose leaders prioritized economic prosperity as the goal of national policy and resisted pressure to remilitarize, would confound a statesman who viewed the world in terms of a more traditional balance of power based heavily if not entirely on military might. He did not seem entirely comfortable with the notion that, as he wrote in Diplomacy, “it was…possible for a country to be an economic giant but to be militarily irrelevant, as was the case with Japan.”

Accordingly, when in office, Kissinger seems to have viewed Japan less as a great power in its own right than as a piece for the United States to move around the global chessboard in the great game he and Nixon were playing with the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China. Nixon and Kissinger’s overtures to China – one of the two so-called “Nixon shocks” – was of course the most significant example of failing to take Japan seriously. Japan, like other democratic US allies, learned of Kissinger’s landmark trip to Beijing only minutes before it was revealed to the public, what Kissinger describes in his memoirs as “the principal sour note” in response to the news, not least because Japanese governments had for years chafed under US pressure to forego explored expanding commercial ties with mainland China.

But they also saw Japan as a “card” to play in this strategic triangle. Seymour Hersh notes how Nixon and Kissinger “[had] been intrigued since early 1969 with the possibility of an independent Japanese nuclear deterrent.” This is not something that they kept to themselves. In 1969, for example, Nixon reportedly raised this in conversation with Prime Minister Satō Eisaku. Hersh recounts:

At that meeting, Nixon and Kissinger broadly hinted to Sato that the United States would “understand” if Japan decided to go nuclear. The only other person present, a State Department interpreter, was troubled by such talk, and leaked his notes to senior officials in the State Department; the notes eventually made their way to Richard Sneider, the former Kissinger NSC aide then serving as Deputy Chief of Mission in the American Embassy in Tokyo. ‘These guys [Nixon and Kissinger] thought they were being cute,’ Sneider says. ‘Sato and his aides walked away confused. We had to go cleaning up the mess and had to tell the Japanese they’d misunderstood what Nixon and Kissinger were saying. We just quietly sabotaged the whole thing.’5

There are conflicting reports that Nixon and Kissinger, when they were exploring their opening to China, warned the PRC’s leaders that if Beijing balked at cooperation against the Soviet Union, they would “let” Japan go nuclear.6 The concerns of Japan’s leaders, to say nothing of the Japanese people, were an afterthought. Satō, after all, had promulgated Japan’s three non-nuclear principles in 1967 and resisted the Nixon administration’s demands to keep nuclear weapons in Okinawa after reversion, resulting in a secret agreement that would allow the US to reintroduce nuclear weapons to Okinawa in the event of a crisis, notwithstanding the non-nuclear principles. Or, for that matter, Japan’s signing of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, for which Satō received a Nobel Peace Prize in 1974. Kissinger continued to be “intrigued” with the idea of a nuclear-armed Japan up until his death, telling the Economist in May 2023 that he expected Japan to go nuclear within five years.7

This debate is a microcosm of the broader reality that Kissinger seemed more comfortable engaging in diplomacy with dictators and authoritarian regimes, instead of messy democracies like Japan or US allies in NATO. As Bergsten writes:

His major foreign sorties have been to totalitarian opposite numbers who could, alone, speak to him for their governments he is reluctant to engage with lots of bureaucratic adversaries on issues in which he is not recognized as the leading authority in town, as would be true in the economic area, especially in the absence of administrative machinery which he can control.

His famous line about Europe – “Who do I call if I want to call Europe?” – exemplifies this impatience with other democracies and their complicated domestic politics.8

To account for his struggles with Japan, Kissinger would repeatedly fall back on cultural essentialism. For example, in The White House Years, he writes:

The amazing thing is that the Japanese respect for the past and sense of cultural uniqueness have not produced stagnation.

…

A Japanese leader does not announce a decision; he evokes it. Westerners decide quickly but our decisions require a long time to implement, especially when they are controversial. In our bureaucracy, each power center has to be persuaded or pressured; thus, the spontaneity or discipline of execution is diluted.

…

The Japanese do not like a confrontation, which produces a catalogue of identifiable winners and losers; they are uneasy with enterprises whose outcome is unpredictable.

…

Of course, there are dark edges to the intricate and close-knit Japanese social structure. It provides the individual Japanese with a defined sense of self and thus brings about restraint and mutual support in the Japanese context; but outside Japan these same people can become disoriented, even ferocious, when the criteria for conduct evaporate in confrontation with alien, seemingly barbarian, behavior.

…

In my view Japanese decisions have been the most farsighted and intelligent of any major nation of the postwar era even while the Japanese leaders have acted with the understated, anonymous style characteristic of their culture.9

“The truth is that neither I nor my colleagues possessed a very subtle grasp of Japanese culture and psychology,” he writes. “We therefore made many mistakes; I like to think that we learned a great deal and ultimately built an extraordinarily close relationship after first inflicting some unnecessary shocks to Japanese sensibilities.” And this view was not limited to his reflections on his time in power. In Diplomacy, he writes of Japan in the post-cold war world, “The role of Japan will inevitably be adapted to those changed circumstances, though, following their national style, Japanese leaders will make the adjustment by the accumulation of apparently imperceptible nuances.”10 Basically, Japan is difficult to understand, its leaders don’t act like other leaders and its political system is opaque, and it refuses to play international politics the way it’s meant to be played.

There is something almost anti-political about this resort to “Oriental inscrutability.” In the 1970s, this view of Japan likely resulted in needless friction and loss of trust that would have consequences for years to come. Meanwhile, it is also a view of Japan that undervalues the ways in which Japan has changed since the end of the cold war. Not only have Japan’s policies have changed – it is hard to argue that leaders like Hashimoto Ryūtarō, Koizumi Junichirō, or, indeed, Abe Shinzō were anonymous, understated, or self-effacing. The reality is that much of what frustrated Kissinger about Japan when he was in power had more to do with the institutions and politics of Japan during the cold war. When the institutions changed – when Japan’s prime ministers acquired significantly more institutional capacity due to Heisei-era reforms – they suddenly discovered the ability to make decisions and follow through. Bureaucratic politics still matter; public opinion still shapes the decision-making environment; and there is no small amount of path dependency, not least in Japan’s security policies. But I thoroughly reject the notion that it is necessary to appeal to Japanese culture to account for how and why Japanese governments make decisions. Indeed, to the extent to this newsletter has a credo, it is the need to take Japanese democracy and its institutions seriously when thinking about Japan’s place in the world.

Therefore, while Kishida may have had his reasons for issuing a statement on Kissinger’s death, we should be clear about one thing. He was not delivering a tribute to Kissinger as a close friend of Japan or a steward of a stronger US-Japan relationship. It would, frankly, be difficult to offer such praise to a man who embodied “Japan passing” avant la lettre.

This is far from the final word on Kissinger’s engagement with Japan. For more on this subject, I will be talking with Daniel Sneider, who has not only had a lengthy career as a foreign correspondent and scholar but also happens to be the son of the aforementioned Richard Sneider, who worked under Kissinger at the NSC, was a key player in the negotiations for Okinawa’s reversion, and also served as Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for East Asia during the Nixon administration. Stay tuned for that video, which will be distributed this week.

Book giveaway!

The expanded paperback edition of The Iconoclast is now on sale outside of the United States. From 20 November to 3 December, you can buy it directly from Hurst Publishers for 50% off as part of their Black Friday sale.

But as a thank you to my readers, I will be giving away a signed copy of the paperback to one subscriber. To enter the giveaway, please send an email with subject line “Iconoclast giveaway” to bookgiveaway@observingjapan.com. I will accept entries until December 15, at which point I will draw a winner.

Pledge your support

As always, many thanks to those who have already signed up to read these posts. At the moment, I do not plan to shift to a subscription model. However, Substack has introduced the option of “pledging,” indicating a willingness to subscribe if I were to shift to a subscription plan. In the event of a snap election, I may charge for electoral analysis and keep other posts publicly available.

If you would be willing to pay for a subscription, it would be helpful if you could press the “pledge your support” button on the upper right of the page. I will not turn on subscriptions without notice, but I would like to gauge how much interest there might be.

He had also met with him in Tokyo as recently as October 2022: https://www3.nhk.or.jp/news/html/20221026/k10013871251000.html.

Both governments, in their haste to defuse opposition to US’s essentially colonial control of Okinawa, conceded a privileged position to the US Military in the prefecture, symbolized by the secret agreement would allow the US to reintroduce nuclear weapons to the prefecture in a crisis, that is at the heart of the Okinawa “issue” today .

The Asahi Shimbun, in its editorial on Kissinger’s death, summarized Kissinger’s record thusly: “Kissinger pursued tough-minded pragmatism, aimed at maximizing national interest by using America’s overwhelming powers, and meticulously developed highly refined and well-calculated strategies for winning the great powers game. But he gave little attention or consideration to the sovereignty and human rights of smaller countries.”

Michael Schaller, Altered States, p. 211-212.

Seymour Hersh, The Price of Power, p. 381.

See Schaller’s discussion of this: Altered States, p. 229-231. Kissinger, in The White House Years, recounted that ahead of his first meeting with Zhou, Nixon said that he wanted him “to emphasize that China’s fear of Japan could best be assuaged by a continuing US-Japanese alliance,” which is a bit more innocuous than Nixon later recalled.

Of course, this makes it particularly awkward that Kishida singled out Kissinger’s role in the Global Zero movement for praise.

Democratic niceties that the Nixon administration would try to sidestep at home, with disastrous results.

This is a representative selection of quotes from various places in The White House Years.

Henry Kissinger, Diplomacy, p. 827.

Well said. Thank you.

Excellent piece