On Saturday, Prime Minister Kishida Fumio removed Matsuno Hirokazu as chief cabinet secretary, the first axe to fall as the prime minister grapples with the campaign finance scandal centered on the LDP’s Abe faction.

On Sunday, it appears that Kishida will move to purge other high-ranking members of the Abe faction. Nishimura Yasutoshi, the minister of economy, trade, and industry; Hagiuda Kōichi, the LDP’s policy chief; Takagi Tsuyoshi, the LDP’s parliamentary affairs chief will all be dismissed. They may be joined by Sekō Hiroshige, the secretary-general of the LDP in the upper house. It is nothing short of a purge of the top leadership of the Abe faction from senior government and party posts.

By moving swiftly to remove the Abe faction leaders who are going to receive the most scrutiny as the investigation continues — NHK, for example, suggests that more than ten Abe faction members may have received the JPY 10mn (USD 69,178) over five years that Matsuno allegedly received and that more than half of the faction’s members received a kickback in some form — Kishida won’t have spend political capital defending officials who would likely have been forced to resign sooner or later anyway. But, having forced them out now, Kishida has also conceded that the scandal is far from groundless, necessarily prompting questions as to whether the Abe faction was alone in skimming off donations to kickback to the faction’s lawmakers.

However, if the corruption scandal is largely contained to the Abe faction, Kishida does have an opportunity to cut himself loose from the Abe faction, whose support ushered him into power and has sustained him ever since, and usher in a new era for the LDP. If he can make this into an Abe faction scandal — and insulate other parts of the LDP from the damage — he might have a chance to claim the mantle of party reform (an issue he campaigned on, after all), rally the public, and build a new base of support within the LDP that excludes the Abe faction. I have my doubts about his ability to pull off this shift, but the opportunity is there.

It is possible that Kishida himself sees this as a way out of his current predicament. There are reports that both Kōno Tarō, the digital affairs minister, and Koizumi Shinjirō, the former environment minister, could be under consideration for the chief cabinet secretary post. If Kishida were to tap either, who have consistently ranked among the most popular politicians in Japan for years, it would at a stroke make party reform a top issue and serve to recast the Abe faction and its allies as a corruption-ridden old guard. It could also serve as a bid to loosen the right wing’s grip on the policy agenda. Recall that Abe and the right wing took a scorched earth approach to Kōno’s candidacy in 2021, when they tarred him as, among other things, soft on China. Were Kishida to make Kōno chief cabinet secretary, it could also change Kōno’s prospects for future leadership contests, whether in 2024 or beyond. As the Kanagawa Shimbun suggests, this moment could mark the ascendancy of Suga Yoshihide as a power behind the throne, as both Koizumi and to a lesser extent Kōno are in the former chief cabinet secretary’s and prime minister’s circle of allies. What they have in common is, if not liberalism, than a loose philosophy of a modernizing, one-nation conservatism committed to good governance on behalf of all Japanese. Kōno, for his part, has already taken to the airwaves to make the case for reforming the LDP’s internal governance.1

Appointing either would be daring and would resonant with the public — while being aggressive towards the Abe faction. Other names floated by the Kanagawa Shimbun as plausible candidates for the chief cabinet secretary job connected with Suga — Katō Katsunobu, Suga’s chief cabinet secretary and holder of multiple posts under Abe, and Tamura Norihisa, minister of health, labor, and welfare under both Suga and Abe — would be more conciliatory. Tapping Katō, a member of the Motegi faction, could also serve to preserve peace with LDP Secretary-General Motegi Toshimitsu.

How Motegi handles the current situation — and how Kishida handles Motegi — is also unclear. As the most plausible successor to Kishida, Motegi has reason to want Kishida to flounder; as the leader of the LDP’s third-largest faction, he has reason to want the Abe faction to stumble and even fracture; and as the LDP’s secretary-general, he has to be careful not to become a casualty of the scandal engulfing the party. An alternative scenario to the “Kishida turns reformist” scenario sketched above would see the prime minister work with Motegi and Asō Tarō to stabilize the situation but avoid a riskier move like throwing his lot in with popular but unpredictable mavericks. This approach might contain the damage from the scandal but would not fundamentally change the outlook for Kishida.

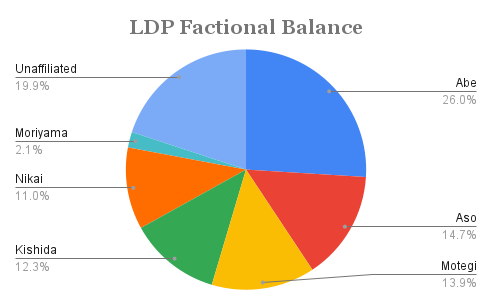

Finally, the days of the Abe faction as the LDP’s dominant bloc appear numbered. The faction, the Seiwa-kai, has dominated the party and Japanese politics for most of the twenty-first century. It has been the largest faction since 2005 and furnished five of the last eight LDP prime ministers (counting Abe twice), who have governed for a combined fifteen years. The campaign finance scandal will at the very least sideline its senior-most leaders for the foreseeable future and, depending on the outcome of the investigation, could remove them permanently from the balance of power in the LDP. It is unlikely that the Abe faction, having struggled to pick a single leader from this group of bosses, will find a unifying figure in its second tier of leaders. The faction’s fragmentation is a real possibility, which could also lead to a scramble among the Motegi and Asō factions in particular for former Abe faction members, as both seek to supplant it as the largest faction.

It is far from certain what the LDP looks like in the wake of this crisis. It seems safe to say that the Abe faction, its top leaders removed from high office and accused of brazen acts of corruption, will be weakened. But remains to be seen whether Kishida and other party bosses will see the scandal as an opportunity for reinvention — perhaps extending the prime minister’s political life — or whether they play it safe and muddle through, redistributing power among the factions but not fundamentally party governance or its identity. We should not assume that Kishida’s cautiousness makes the latter a foregone conclusion. Kishida has generally played it safe, but he has occasionally showed a bold streak, not least when he launched his leadership bid in 2021.

Book giveaway!

The expanded paperback edition of The Iconoclast is now on sale outside of the United States but can be purchased directly from Hurst and shipped anywhere outside of the European Union.

But as a thank you to my readers, I will be giving away a signed copy of the paperback to one subscriber. To enter the giveaway, please send an email with subject line “Iconoclast giveaway” to bookgiveaway@observingjapan.com. I will accept entries until December 15, at which point I will draw a winner.

Pledge your support

As always, many thanks to those who have already signed up to read these posts. At the moment, I do not plan to shift to a subscription model. However, Substack has introduced the option of “pledging,” indicating a willingness to subscribe if I were to shift to a subscription plan. In the event of a snap election, I may charge for electoral analysis and keep other posts publicly available.

If you would be willing to pay for a subscription, it would be helpful if you could press the “pledge your support” button on the upper right of the page. I will not turn on subscriptions without notice, but I would like to gauge how much interest there might be.

Kōnō, given his involvement in the unpopular My Number card rollout, would not be without liabilities, but his political value to Kishida could still be significant.