Thank you for reading Observing Japan. This post is available to all readers.

If you are looking for timely, forward-looking analysis of the stories in Japans’s politics and policymaking that move markets, I have launched a new service through my business, Japan Foresight LLC. For more information about Japan Foresight’s services or for information on how to sign up for a trial or schedule a briefing, please visit our website or reach out to me.

After a fifteen-day campaign that at times seemed to lack energy, the LDP leadership election delivered a stunning finale. When Takaichi Sanae stormed past Ishiba Shigeru to take first in the first round of voting – not only surpassing him to finish only three votes behind Koizumi Shinjirō in the LDP lawmakers vote but also winning the rank-and-file vote by one vote – it seemed like Takaichi’s victory was all but assured. Given Ishiba’s well-known difficulties in securing the support of parliamentary colleagues in previous leadership bids, it seemed that Ishiba’s chances were slim. Markets certainly thought so, as the yen weakened sharply in light of Takaichi’s criticism of the Bank of Japan’s interest-rate hikes.

But in the end, Ishiba managed to exorcise his defeat of 2012, when Abe Shinzō came from behind to defeat him in the runoff, beating Takaichi Sanae, Abe’s intellectual successor, by a slender 215-194 margin, clearing a majority by seven votes. The LDP’s leadership election ended up being as dramatic as promised, delivering a remarkable and unexpected result and producing a new leader who might actually represent a new path for the LDP.

Here, in no particular order, are some initial thoughts about Ishiba’s stunning victory.

We will have to see more on how lawmakers vote in the second round, but I can think of a lot of reasons why Ishiba was able to pull out the victory. First, with two national elections coming, some LDP lawmakers may simply have viewed their chances with Ishiba as better than with Takaichi, even with her strong performance with LDP rank-and-file members. Second, there may actually have been plenty of lawmakers who preferred his approach to political reform compared with Takaichi’s desire to just move on from the scandals, not least because the latter could be a loser in elections. Three, I wonder whether some LDP lawmakers were thinking about the matchup with Noda Yoshihiko and whether Ishiba would fare better head to head against a Constitutional Democratic Party pivoting in a conservative direction. Four, Takaichi is an outlier, not least on economic policy, where she was preparing for battle with the Bank of Japan. Ishiba, who pledged to continue Prime Minister Kishida Fumio’s policies, was a safer choice. Finally, given that the next prime minister will immediately face a challenging international situation, I wonder whether that advantage ultimately played in Ishiba’s favor.

On that note, I think we can reach some initial conclusions about what Ishiba foreign policy might look like. His victory is good news for continuity in the Japan-South Korea relationship. Regarding the relationship with China, he clearly wants Japan to be able to defend itself, but he will be more prepared to build on the tentative steps to stabilize the bilateral relationship than Takaichi would have been, particularly after the fatal stabbing in Shenzhen. On the relationship with the United States, clearly Ishiba has changes he would like to make in the alliance, but presumably he will not be able to do much before the US presidential election.

In the near term, I do not think we should expect any dramatic shifts from Ishiba on economic policy. He will respect the BOJ’s independence, creating more room for additional interest rate hikes; he will be more inclined to moving towards fiscal discipline, but not immediately; he will look for a way to eventually raise taxes to pay for defense spending increases and to fund redistribution through corporate and wealth taxes; and will look to reorient growth strategies towards poorer, more rural regions. But substantial changes will take time, and they will take political capital.

On the question of political capital, the biggest question is how Ishiba will govern a divided party. He is governing a party with a substantial minority that favored a candidate whose views are dramatically different from his own. Will Takaichi and her backers play a role in his government and party executive? For that matter, how will he govern the party in a post-factional era? Maybe a general election early in his tenure resolves some of these issues, but party governance will determine whether he can endure or whether his tenure is brief.

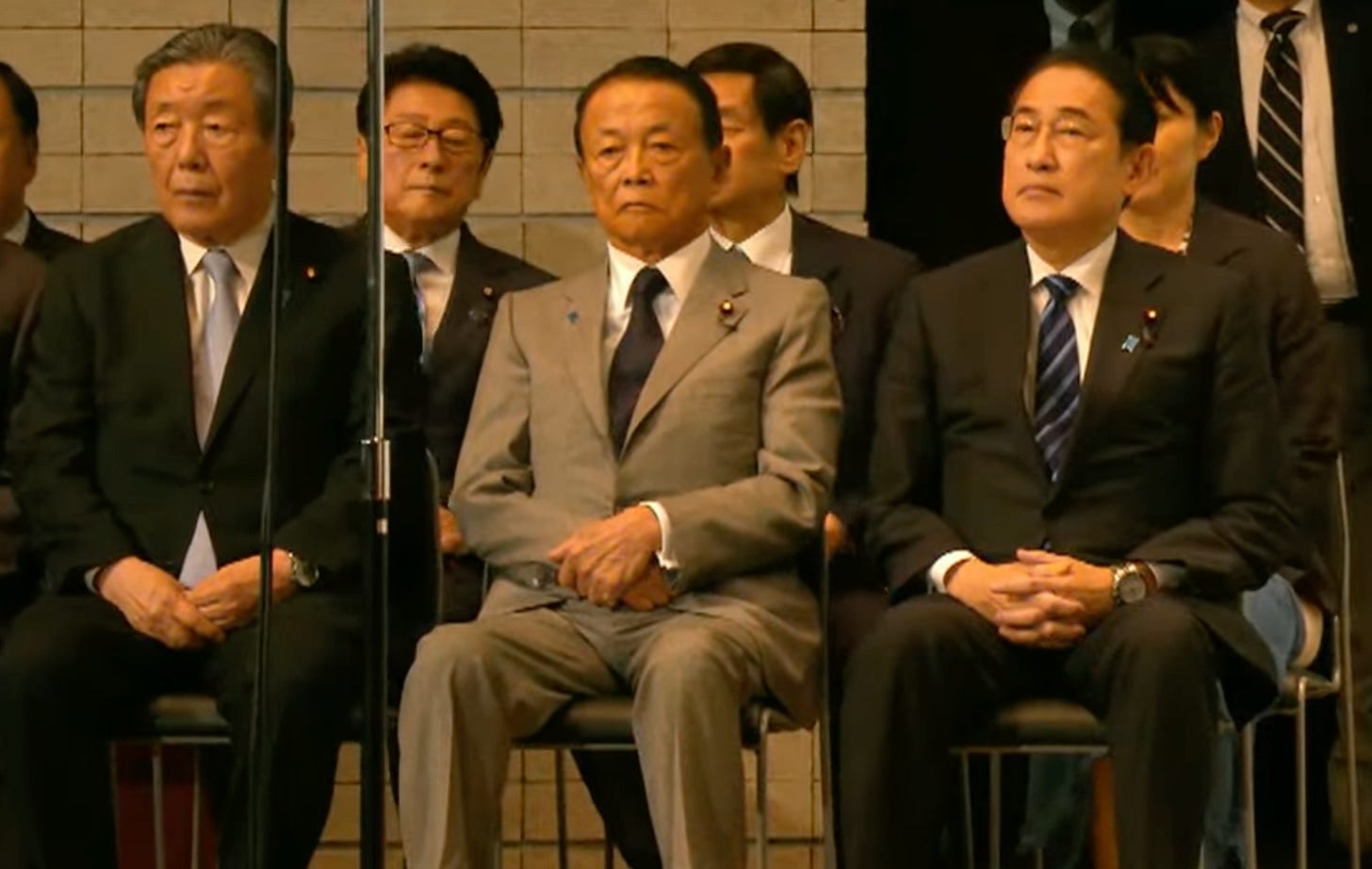

In general, compared with Kishida, who depended on both the Abe and Asō faction for support and was therefore constrained, Ishiba will not face the same constraints. What was once the mainstream of the party will be the anti-mainstream (as they say in Japanese political lingo).

Koizumi’s third-place finish was disappointing but not unexpected. The polls, particularly of rank-and-file members, were pointing to a third-place finish. Whether this was a genuine drop in his support or the result of the later surveys reflecting the views of actual voting LDP members – who in all likelihood skewed older and therefore less amenable to Koizumi – his gamble was costly. His career is far from done, and he will likely learn from the experience, but he does not emerge untarnished. Presumably he is in line for a cabinet post under Ishiba, though.

Kōno Tarō’s eighth-place finish is enormously disappointing compared to his performance in 2021, but it was not unexpected. His gamble on Asō did not pay off, to say the least, and I wonder how much longer he will remain in the Asō faction, particularly after the faction boss abandoned him hours before the vote.

Of course, Asō’s very public bet on Takaichi did not pay off. It may have helped her advance to the second round – given that she leaped to second among lawmakers in the first round – but he threw his weight behind her to block Ishiba and/or Koizumi and he still winds up with his old adversary Ishiba as prime minister. But then, maybe he sensed that the ground might be prepared to shift in Ishiba’s direction. I wonder how many Asō faction members wind up with jobs in the Ishiba cabinet.

Kishida will likely remain an important player under an Ishiba government, at least more than he would have had under a Takaichi government.

Will Takaichi run again in the next leadership election? I assume Kamikawa Yōko will not make another leadership bid. Will Ishiba support the advancement of female political talent? He had no women among his twenty endorsers.

In general, Takaichi showed both that it was a mistake to underestimate her – she clearly has a strong and passionate following at the grassroots level – but that there were also enough doubts about her as prime minister that Ishiba was able to prevail.

Will the next LDP election be the generational change election? Ishiba is yet another prime minister who came of age politically in the 1990s. Presumably he will be the last of that generation to govern.

Should we now expect a general election in November rather than late October? I have no doubt that Ishiba will want to move quickly to a snap election – he will likely enjoy robust support in the polls – but he also criticized Koizumi for suggesting that he would call a snap election before a proper debate in the Diet.

I am sure that I will have more thoughts about Ishiba’s comeback victory as more reporting emerges about how he pulled it off. But there is more than enough to think about at the moment.