Thank you for reading Observing Japan. This post is available to all readers.

If you are looking for timely, forward-looking analysis of the stories in Japans’s politics and policymaking that move markets, I have launched a new service through my business, Japan Foresight LLC. For more information about Japan Foresight’s services or for information on how to sign up for a trial or schedule a briefing, please visit our website or reach out to me.

To mark the first anniversary of the launch of the paid Observing Japan newsletter, all new subscriptions are 20% off through 22 March. Click below for a discount on access to paid content, which will include participation in conference calls with paid subscribers, with the next planned for the week of 17 March. Stay tuned for more details.

Ishiba Shigeru is not having a great March. He had a good February, delivering victories in the two most indispensable areas for his survival. He had a successful summit with Donald Trump, dispelling for the moment concerns that he would be unable to hold his own with the US president. And the ruling coalition’s multi-track negotiations with the three main opposition parties eventually yielded a compromise with Ishin no Kai that ensured the budget’s passage through the House of Representatives, albeit not fast enough to guarantee the budget’s passage by the Diet before the end of the fiscal year regardless of what happens in the upper house.

Since the budget moved to the upper house last week, however, Ishiba has stumbled. In the face of criticism from patient advocacy groups, opposition parties, and even Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) lawmakers, he shelved a plan to raise the cap on out-of-pocket expenses for high-cost medical care, which will necessitate a change in the budget before it can be passed. Meanwhile, Mutō Yōji, the minister of economy, trade, and industry, reported home empty-handed from his mission to Washington in pursuit of exemptions from impending steel and aluminum tariffs, which went into effect on Wednesday with no exemptions. Mutō also received no guarantees of exemptions from next month’s automobile and “reciprocal” tariffs.

Politically, his efforts to use the LDP’s convention on Sunday, 9 March to turn the page on the party’s kickback scandal and begin the work of rebuilding public trust in the party was overshadowed by signs of internal dissent. Kobayashi Takayuki, angling to become the standard barrier of the LDP’s conservative wing, criticized Ishiba’s reverse course on the medical expenses cap as indicative of a deficient policy process and said it is not at all clear what policies lie behind his “pleasant Japan” slogan. Meanwhile, Nishida Shōji, an arch-conservative upper house member allied with Takaichi Sanae who is up for reelection in July, said on Wednesday, 12 March that the party cannot contest the upper house election under Ishiba’s leadership and that he should resign after the budget passes the Diet.

Finally, on top of the rumblings of discontent within the LDP, on Monday NHK released its latest poll showing that the slight bump that the prime minister received after his summit with Trump evaporated, with an eighteen-point swing in net approval from +9 to -9. The LDP’s numbers did not shift nearly as much, falling by 2.1%. NHK’s analysis shows that the biggest drops were among independents, whose support for the Ishiba government dropped thirteen points to 23% and among virtually all age brackets except those aged eighty and above. Particularly notable is that Ishiba’s handling of the budget process, which has generally received good marks from the public, graded out relatively poorly with only 43% greatly (3%) or somewhat (40%) approving of the passage of a revised budget through the lower house compared with 48% greatly (14%) or somewhat (34%) disapproving.

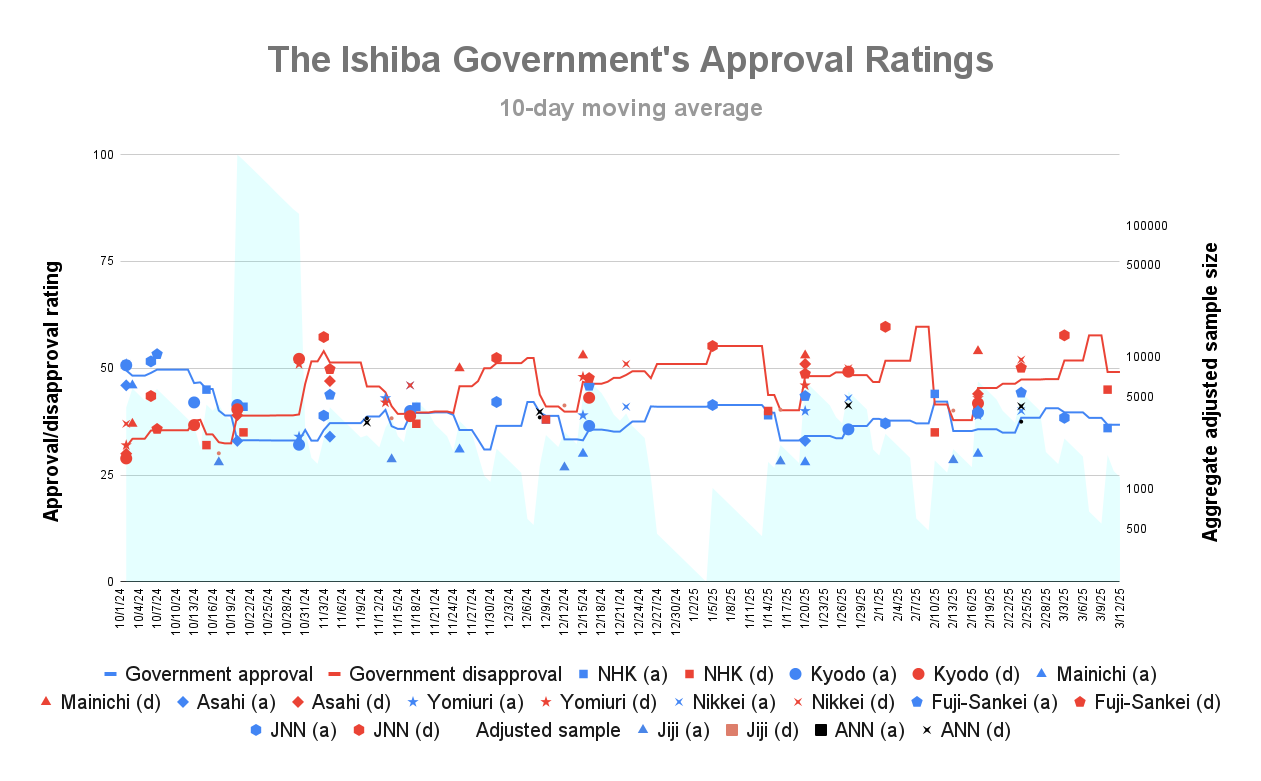

Despite this string of bad news, however, it is too early to write Ishiba off. First, as bad as the NHK poll looks, it has essentially reset the government’s approval to where it was before the summit. In my ten-day moving average of the government’s support, the government’s net approval was at -14 on 6 February, the day before the summit. After the summit, he got a bump that brought net approval to virtually even. Subsequently it has drifted back down and by 3 March it was at -12. In my average, the new NHK poll barely moved the needle, shifting net approval by roughly two-tenths of a percentage point. Perhaps more importantly, while Ishiba’s net approval has fluctuated, it has largely been due to variance in his disapproval ratings, which have a standard deviation of 5.23 percentage points around an average of 47.81% since the general election last year. By contrast, his approval ratings have a standard deviation of only 2.72 percentage points around a mean of 37.52%. Even just glancing at the chart, it is apparent that there have been bigger swings in disapproval than in approval, which may be due to different polling methodologies or sampling errors.1

Thus, the NHK poll in and of itself should not lead Ishiba to panic. Indeed, it is not even the worst poll since the start of the month, as the government’s net approval in the Japan News Network poll released on 3 March recorded a -19.3 net approval, driven largely by an unusually high disapproval rating of 57.7% compared to a slightly above average approval rating of 38.4%.

What about the vocal criticism from Kobayashi and Nishida? Here too, some context is important. For starters, both are particularly outspoken members of the LDP’s right wing, which has, of course, very little love for the prime minister and has been waiting for him to stumble. Meanwhile, if the right wing were to try to organize a rebellion against Ishiba, this is precisely the time when they would have to do it. It would already be less than ideal to replace the party leader and prime minister in the middle of the Diet session, and the closer the two elections – the Tokyo metropolitan assembly elections as well as the upper house elections – get, the more likely it is that the chaos of a sudden leadership change would hinder rather than help the party’s campaigns. If LDP dissenters cannot either force Ishiba to resign or round up a majority to motion for an early leadership election by early April, it will be all but guaranteed that Ishiba will lead the party into the summer elections. Given that Ishiba seems unlikely to quit voluntarily in the next two weeks, anti-Ishiba forces will have to organize a rebellion if they want a leadership change.

It bears stressing just how difficult it is to launch a rebellion against a sitting party leader who does not want to resign voluntarily: it takes a majority of the party’s lawmakers plus representatives of the forty-seven prefectural chapters to vote to move forward a party leadership election, essentially an invitation to the party president to leave. The LDP’s right wing could not organize a majority to elect Takaichi as party leader in September, and subsequently had its ranks thinned in the general election. To succeed, a rebellion would necessarily have to flip Ishiba voters. Thus far, we have not seen any publicly wavering Ishiba voters. Meanwhile, there is not a single standard bearer for the anti-Ishiba forces. Both Kobayashi and Takaichi have been outspoken in recent weeks. Would one or the other be willing to step aside? And if they were to push Ishiba aside, there is no guarantee that they might end up losing to say, Chief Cabinet Secretary Hayashi Yoshimasa, who finished fourth in last year’s leadership election and who the right wing dislikes at least as much as they dislike Ishiba.

To be sure, the political situation is fluid. The possibility of some kind of foreign policy or economic shock in the next several weeks is perhaps higher than Ishiba might prefer. The Diet is preparing for debates on two issues – separate surnames for spouses and the next round of campaign finance reform – that could divide the LDP against itself and against Kōmeitō, with Ishiba potentially pitted against the LDP’s right wing on both issues. It may be worth contemplating the (unlikely) possibility that friction over these issues could a) lead opposition parties to submit a no-confidence motion and b) lead the right wing to either abstain from or approve of the motion, triggering a full-blown crisis that could destroy Ishiba’s government and break the LDP. Notwithstanding positive developments in the spring wage negotiations, the public’s frustrations about rising inflation continue and are a real concern for the LDP heading into the summer’s elections. All of which is to say that Ishiba may not have much margin for error, which undoubtedly accounts for his hasty pivot on the medical expenses cap.

Nevertheless, his situation is still not desperate. His approval ratings are still largely in line with where they have been for most of his tenure and nowhere near low enough that he would have to consider resignation. And absent a voluntary departure by the prime minister, his rivals in the LDP appear to be nowhere near organized enough to make him go. Thus, it may still be premature to bet against Ishiba’s survival, at least until the voters have their say again.

One of my goals for this project going forward is to start measuring and incorporating house effects to account for systematic biases in each poll in the sample.