Thank you for reading Observing Japan. This post is available to all readers.

You can find an earlier post on election returns here. You can follow the very lively chat among Observing Japan readers here.

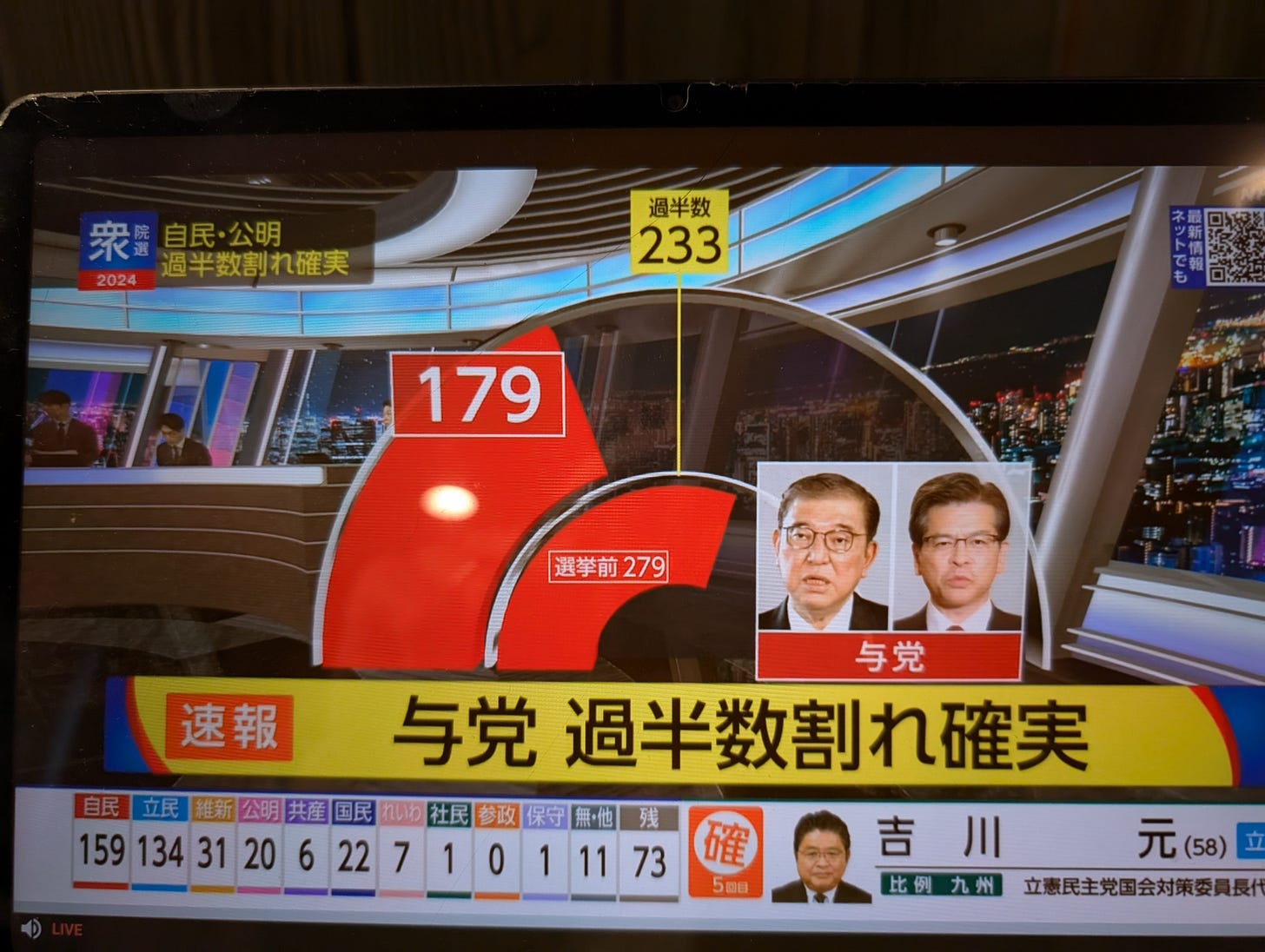

At approximately 12:30am JST, NHK posted a breaking news alert. The LDP and Kōmeitō would not achieve their “victory line” of 233 seats, a simple majority in the House of Representatives.

The result is that the Japanese political system is indeed entering a new and uncertain period. The five major parties – the LDP, Kōmeitō, the Constitutional Democratic Party, the Democratic Party for the People (DPFP), and Ishin no Kai, which together hold 401 seats and counting the new lower house – will now have to negotiate amongst themselves to assemble a majority that can select a prime minister and cabinet and manage the legislative process. As of this writing, with five seats still to be called by NHK, the LDP and Kōmeitō have 214 seats, nineteen short of a simple majority. The CDP, DPFP, and Ishin have 211 seats.

It will not be easy, and it is difficult to figure out a configuration that surpasses the 244-seat “stable majority” line that would give the government control of committees. The leaders of the CDP, DPFP, and Ishin have all said before the general election that they would not be interested in joining the LDP-Kōmeitō coalition, although DPFP leader Tamaki Yūichirō suggested that cooperation on an issue-by-issue basis is possible. Meanwhile, Kōmeitō, whose new leader Ishii Keiichi lost his race in Saitama-14 and will not return to the Diet since he was not listed simultaneously as a PR candidate, has suffered some significant losses, particularly in Osaka, and may be weighing its options.

At this point, there are four possible outcomes of post-election negotiations.

1) LDP-Kōmeitō minority government, with limited external cooperation with the DPFP and/or Ishin: probably the most likely outcome, but not a particularly stable outcome, with the government that emerges fragile, vulnerable to a no-confidence motion if it does not satisfy opposition demands on political reform but also vulnerable to intra-LDP conflict.

2) LDP-Kōmeitō-Ishin and/or DPFP coalition government: it is not impossible that either Ishin or the DPFP shifts its thinking on a coalition, depending on what policy promises or positions the LDP and Kōmeitō offer (or even the premiership for Tamaki, as mentioned yesterday), but neither party seems inclined to help the LDP at this point. Any talks between these parties in the coming days bear close scrutiny, as either would have enough seats to secure a majority.

3) LDP-Kōmeitō-CDP grand coalition: CDP leader Noda Yoshihiko ruled this out before the general election, and there is little reason to think that, having just scored major gains at the LDP’s expense by campaigning against the LDP’s corrupt practices. The party will likely keep the pressure on the LDP heading into upper house elections next year, and look for an opportunity to deploy a no-confidence motion at a moment of maximum strategic advantage.

4) CDP-Ishin-DPFP coalition: Depending on where the parties wind up, this option may not be realistic anyway, at least not without Kōmeitō or some LDP breakaway group joining with them. But even if somehow the three parties could reach a majority, the negotiations might be even more difficult than LDP-Kōmeitō negotiations with these parties. It may be difficult for these parties to agree on anything other than certain political reforms, to say nothing of the distribution of posts.

The parties will now have no more than thirty days, as mandated by the constitution, to figure out a configuration that can form a new government.

Who will lead that government, particularly if it is an LDP-led government? Whether or not Prime Minister Ishiba Shigeru resigns as LDP leader today, it seems unlikely that he will survive to lead a new government as prime minister, the losses being significant enough to make it difficult for him to escape responsibility, though it is possible that he could stay on as a caretaker if it is difficult to find an acceptable alternative. For his part, Ishiba has said he intends to stay on. If he quits, at this point, it would be premature to assume that Takaichi Sanae, runner-up in the September leadership election, will be the next LDP leader. Given the likely fragility of the next government – as well as the tensions within the LDP’s ranks – it is more likely that a compromise candidate like Finance Minister Katō Katsunobu, who has ties with both the party’s conservatives and reformists, emerges as a consensus candidate than Takaichi takes the leadership herself, particularly given that a) the party’s losses may well have disproportionately affected her base in the party and b) she has been a poor messenger on political reform. But it could take time for this process to unfold. The LDP would need to move quickly to replace Ishiba and manage coalition negotiations, favoring a consensus candidate.

There will be more sifting through the data in the coming days, but we can reach a few early conclusions. First, the turnout rate is estimated at somewhere below 54% lower than 2021 by several points and not much higher than 2014’s record low. In other words, the CDP engineered significant electoral gains without bringing out a significant number of independents, which the Democratic Party of Japan did in its 2007 upper house and 2009 general election victories. Exit polls suggest that the CDP did not necessarily win a significantly larger share of the independent vote. In Kyodo’s exit poll, the party took 25.2% of the independent vote, compared with 24.2% in 2021, and independents were only 14.6% of the electorate. But only 69.7% of the LDP’s supporters – who were 31.8% of the electorate – voted for their party, with 7.1% voting for the CDP and 6.2% voting for the DPFP, both more than the 5.9% of LDP supporters who voted for Kōmeitō. Those numbers are probably sufficient to explain the outcome and suggest that Noda’s comeback – engineered at least in part by Ozawa Ichirō – may have been the right move to bring around enough disaffected LDP voters to swing marginal races. Meanwhile, the Asahi Shimbun’s exit polling suggests that even with multiple opposition candidates in a majority of districts, independents tended to cluster around the CDP’s candidates, pointing to perhaps greater strategic voting than in the past.

Second, while the ruling coalition’s falling short of the majority means a new configuration of power in the near term, these election returns suggest that Japan’s longer term political crisis is far from over. Lower turnout suggests that almost a majority of voters remain so dismayed by their choices that they are choosing to stay home instead of vote. There is little to suggest that the CDP has, for example, captured the imaginations of young voters. For too many voters, the political system is not delivering, and if this marks the beginning of weaker, shorter-lived governments, voters are unlikely to become less disenchanted with Japan’s political parties. It is not entirely hopeless, however. A record of seventy-three women were elected, surpassing the fifty-four elected in 2009.

Third, there are meaningful shifts within the electorate and the party system. Kōmeitō fell significantly short of its pre-election total of thirty-two seats, having been wiped out in Osaka as well as having its leader lost his Saitama constituency. The party will continue to grapple with its dwindling power as a vote-gathering machine. On the left, it is possible that the JCP will be passed by the Reiwa Shinsengumi, pointing the latter’s ability to attract new voters on the left while the former’s base ages. Ishin failed to expand beyond its Osaka stronghold – winning only four single-member districts outside of Osaka – but it also swept the prefecture’s nineteen districts, suggesting that it remains a potent force even after recent setbacks in local elections. The DPFP, meanwhile, nearly quadrupled its seat total, suggesting that its brand of moderate centrism will also have a place. Meanwhile the right-wing populist parties looking to gain a foothold – the Conservative Party of Japan and the Sanseitō – both underperformed relative to expectations, suggesting that at least for now voters are not looking to the right wing as the answer to Japan’s difficulties.

This situation will be fluid for days and weeks to come as the parties work through this new reality. After twelve years of political stability, Japan has entered a new period of political uncertainty. Stay tuned for more updates as this situation unfolds.